Image by Kevin Doncaster*

In 2009 two health experts published an influential book that resonated well beyond their field of interest; it was called The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better (the sub-title was later changed to the less strident, Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger). It argued that inequality has all kinds of negative outcomes on society such as erosion of trust, poor health, and encourages over-consumption. Like many provocations, it divided opinion; these accorded to the rigour of the analysis and unsurprisingly along political lines. Those critical of their argument, as always, didn’t tend to come from the poorer in society, and were bolstered by disingenuously wrapped up as being objective. Thatcher’s biographer, Charles Moore said it was “more a socialist tract than an objective analysis of poverty,” which give its greater strength in my book. And as the authors wrote in 2014, “It is hard to think of a more powerful way of telling people at the bottom that they are almost worthless than to pay them one-third of one percent of what the CEO in the same company gets.”

Sourced from ADiamondFellFromTheSky

There used to be a term that described the wealth gap in society; “how the other half lives”. I have a book with that title by the photographer Jacob Riis that includes one hundred photographs of the slums of New York at the turn into the 20th century. I am not sure it has even been an equal split between the haves and have nots, but as the rich get richer, the politics of democracy has become more binary. The Yes/No paradigm we have today in the outcome of how we vote seems to be driven by the negative – an ‘us against them’, even though it is not so clear who either side is. Danny Dorling, who for many years has studied the effects of inequality on societies, published a paper showing that of the richest 25 nations, the UK and US were the most unequal. He concluded the paper by saying that if you don’t believe the effects this has on societies, essentially, “go see for yourself what it is like to live in a more affluent nation where people are more similar to each other economically. See how they treat each other, the extents to which they trust or fear each other. Spend a little longer living there and see how it might also change you. Explore!”

For those of us not able to do so, we are very lucky to have the likes of multi-talented Jemima Foxtrot who in a poem from her debut collection, All Damn Day, does what a lot of great poets do, allows us to dream. She takes a somewhat Manichean outlook that fits with the division we all feel in what we would like to do: “A half of me wants to exist in a tepee,/breed children who can braid hair and catch rabbits./Drink cocoa from half Coke cans twice a year/on their birthdays, the edges folded inwards/to protect their sleepy lips, cheap gloves to buffer their fingers,/precious marshmallows pronged on long mossy sticks.” However, such ‘rural and romantic poverty’ does not always fit with present circumstance, so we dream elsewhere. “If I were rich/I’d eat asparagus and egg,/in my Egyptian-cotton-coated bed, for breakfast. Bad. Ass./You’d find me in my limo, got a driver called Ricardo,/wears a nice hat. That’s that. Bad. Ass.” And in this dream we may travel to such places as Dorling suggests, but Jemima insightfully shows what lies at the heart these ‘hypocrisies’ we sit in, and how a division of one half or another can lead us all to a false sense of what it is we are after. “Capital has split my dreams in two /like a grapefruit./And I want both. And I want both.”

For those of us not able to do so, we are very lucky to have the likes of multi-talented Jemima Foxtrot who in a poem from her debut collection, All Damn Day, does what a lot of great poets do, allows us to dream. She takes a somewhat Manichean outlook that fits with the division we all feel in what we would like to do: “A half of me wants to exist in a tepee,/breed children who can braid hair and catch rabbits./Drink cocoa from half Coke cans twice a year/on their birthdays, the edges folded inwards/to protect their sleepy lips, cheap gloves to buffer their fingers,/precious marshmallows pronged on long mossy sticks.” However, such ‘rural and romantic poverty’ does not always fit with present circumstance, so we dream elsewhere. “If I were rich/I’d eat asparagus and egg,/in my Egyptian-cotton-coated bed, for breakfast. Bad. Ass./You’d find me in my limo, got a driver called Ricardo,/wears a nice hat. That’s that. Bad. Ass.” And in this dream we may travel to such places as Dorling suggests, but Jemima insightfully shows what lies at the heart these ‘hypocrisies’ we sit in, and how a division of one half or another can lead us all to a false sense of what it is we are after. “Capital has split my dreams in two /like a grapefruit./And I want both. And I want both.”

Jemima Foxtrot was shortlisted for the Arts Foundation Spoken Word Fellowship 2015. Jemima performs extensively across the country. All Damn Day, Jemima’s first collection of poetry was published by Burning Eye Books in September 2016. Jemima has written many commissions including for the Tate Britain, the BBC, the Tate Modern and Latitude Festival. Her poetry film Mirror, commissioned by BBC Arts as part of their Women who Spit series, was available on iplayer for over a year. She has also appeared on Lynn Barber’s episode of Arts Night on BBC2 and on the Tate Modern: Switched on programme on BBC 2 in June this year with a poem especially written to celebrate the opening of the Tate Modern’s new wing. Jemima’s debut poetry show Melody (co-written with and directed by Lucy Allan), won the spoken word award at Buxton Fringe Festival 2015 and was critically acclaimed at its run at the PBH Free Fringe at Edinburgh 2015, receiving several excellent reviews. Melody was runner-up in the Best Spoken Word Show category at the 2016 Saboteur Awards.

Untitled (from All Damn Day)

Capital has split my dreams, a grapefruit cut in two,

the separate segments of both lives glimmering

like a new breakfast.

A half of me wants to exist in a tepee,

breed children who can braid hair and catch rabbits.

Drink cocoa from half Coke cans twice a year

on their birthdays, the edges folded inwards

to protect their sleepy lips, cheap gloves to buffer their fingers,

precious marshmallows pronged on long mossy sticks.

Wrap them in goatskin. Leave them giggling

into drowsiness beneath the pink sky.

A half of me wants to exclude myself

– me and some rugged, clever fella –

live in a converted, cramped van. Grow rosemary

and only own two dresses.

Sandals for the summer, boots for the snow.

Pick mushrooms and save them to trip from in springtime.

Oh, rural and romantic poverty!

Lobster pots, gas lamps, home-grown tobacco,

card games, pine cones,

mussels form the shoreline filled with grit. This is it!

It has to be. Or something close to some of it.

I live in London.

And so yes.

And so yes, still the other half appeals to me.

If I were rich

I’d eat asparagus and egg,

in my Egyptian-cotton-coated bed, for breakfast. Bad. Ass.

You’d find me in my limo, got a driver called Ricardo,

wears a nice hat. That’s that. Bad. Ass.

And if anything important breaks, there’s boy around to fix it.

I’d hire the world’s best campaigner

to make everyone a feminist.

It feels so much more comfortable to sit in these hypocrisies when

they’re quilted.

And I’m in my penthouse in the middle of Paris,

or Tokyo, or Istanbul.

The list of places that I’d like to go is endless and still growing.

But I’m rich now so don’t give a shit about emissions.

I’d buy pink marigolds, plastic crystal on the finger,

fake fur around the cuffs, to pretend to my friends

that – even though I’m rich now –

I still do my own washing-up.

Do I fuck.

My au pair’s name is Clare, she’s hilarious.

Clare’s on the pots, I’m in the hot tub.

Or on my private beach in Thailand

or asleep in the Chelsea Hotel.

Quaffing fine white wine,

scoffing oysters and the choicest cuts of beef.

There’s never much grumbling going on.

Restaurants, day-spas, massages, culture, wish fulfilment.

After lunch I’ll take the glider for a fly or got out to buy

a massive pile of overpriced designer tat.

That’s that. Bad. Ass.

Capital has split my dreams in two like a grapefruit.

And I want both. And I want both.

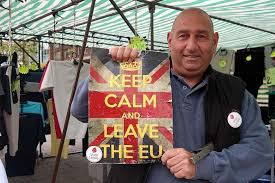

* Image by Kevin Doncaster

It is essential to make the reader believe there is but one type of working class person; they can be of a different age but they must look related, ideally inbred. The main type will be a saggy clothed, got a loyalty card from Sports Direct, Union Jack pale-faced male who claims he can trace his ancestors back to Neanderthal times, which in reality is just before the Second World War when his great granddad ran off with a Polish woman – but don’t talk about that obviously. Always have them accompanied by a muscle shaped dog, preferably tight-leashed, with a 70s punk rock sell-out dog collar, white drooling jaw, and a ravenous appetite for the calf-muscle of an outsider, which is basically anyone born within a mile of their ends.

It is essential to make the reader believe there is but one type of working class person; they can be of a different age but they must look related, ideally inbred. The main type will be a saggy clothed, got a loyalty card from Sports Direct, Union Jack pale-faced male who claims he can trace his ancestors back to Neanderthal times, which in reality is just before the Second World War when his great granddad ran off with a Polish woman – but don’t talk about that obviously. Always have them accompanied by a muscle shaped dog, preferably tight-leashed, with a 70s punk rock sell-out dog collar, white drooling jaw, and a ravenous appetite for the calf-muscle of an outsider, which is basically anyone born within a mile of their ends. With females, try to find a young heavily made up woman in her late teens, early twenties at most, with a neck tattoo and a ciggie hanging from her botoxed lips. She must be pushing a pram, if possible with a brown skinned baby inside wailing its lungs out. Even better if she also has slightly older offspring biting at her heels.

With females, try to find a young heavily made up woman in her late teens, early twenties at most, with a neck tattoo and a ciggie hanging from her botoxed lips. She must be pushing a pram, if possible with a brown skinned baby inside wailing its lungs out. Even better if she also has slightly older offspring biting at her heels.

old medieval days, even though many of them died before the age of five and none of the adults had their own teeth; why do you think they like soup so much? Then move on to Brexit and listen to the range of opinions on this newly found independence, from ‘we can now take our country back’ to ‘we can now send them back’. Pretend to take copious notes at this point to induce a feeling they are finally being listened to.

old medieval days, even though many of them died before the age of five and none of the adults had their own teeth; why do you think they like soup so much? Then move on to Brexit and listen to the range of opinions on this newly found independence, from ‘we can now take our country back’ to ‘we can now send them back’. Pretend to take copious notes at this point to induce a feeling they are finally being listened to.

This sets aside the history they have lived through and the people they became because of it; a World War to monumental technological change from the TV to virtual reality. They have so many stories to tell and be told, and Beth McDonough’s eponymous poem ‘St Fergus Gran’ does just that. “Great Gran lived in weighty old pennies, dropped/from bonehard hands to my fat-cup palm/just before we’d journey west.” Like many stories, hers is one that is handed down the generations, “I never knew of her second sight/All those deaths, and how she kent/her brother lived, when the telegram said not.” Their lives weren’t a straightforward one of getting married and having children; war put pay to that. “I met the East End Glasgow lad she’d/fostered in the war, with all his tricks, his walk/to her from the west coast up to Buchan.” Here Beth tells us a little more about the poem:

This sets aside the history they have lived through and the people they became because of it; a World War to monumental technological change from the TV to virtual reality. They have so many stories to tell and be told, and Beth McDonough’s eponymous poem ‘St Fergus Gran’ does just that. “Great Gran lived in weighty old pennies, dropped/from bonehard hands to my fat-cup palm/just before we’d journey west.” Like many stories, hers is one that is handed down the generations, “I never knew of her second sight/All those deaths, and how she kent/her brother lived, when the telegram said not.” Their lives weren’t a straightforward one of getting married and having children; war put pay to that. “I met the East End Glasgow lad she’d/fostered in the war, with all his tricks, his walk/to her from the west coast up to Buchan.” Here Beth tells us a little more about the poem: