Uncategorized

Affrilachian Poetry: Breaking another Stereotype

For those of you in the UK who were born in the 50s you may have seen the US TV show Beverly Hillbillies, embodied in the Clampett family, who became rich through the discovery of oil, as the lyrics of the theme tune demonstrated.

“Let me tell you a story ’bout a man named Jed: Poor mountaineer barely kept his family fed. … and then one day he was shootin’ out some food … and up from the ground came a bubblin’ crude.”

For those of us born a little later, the 1973 film Deliverance was another gateway to the life of Appalachian poor. A film about some city men who want to experience the back woods and rivers of the countryside but bump up against ‘rednecks’ (‘squeal like a pig boy’- if you know you know), and most famously where one of the men plays guitar with a young local boy on the banjo who outplays him; known as the duelling banjos scene.

For those of us born a little later, the 1973 film Deliverance was another gateway to the life of Appalachian poor. A film about some city men who want to experience the back woods and rivers of the countryside but bump up against ‘rednecks’ (‘squeal like a pig boy’- if you know you know), and most famously where one of the men plays guitar with a young local boy on the banjo who outplays him; known as the duelling banjos scene.

In these programmes and films, Appalachian people are seen as uneducated, poor and unlawful. A lot of very good Southern gothic literature comes from the region, and Savanah Alberts has written a great article, ‘Hootin’ and Hollerin’: The Portrayal of Appalachians in Popular Media, which kicks back against the negative stereotypes.

What is most striking to me now looking back, is that all the characters were white. Yet, African Americans make up 10% of Appalachia (a long spine of mountain area from central Alabama, northeast into southern Canada). For a hundred and fifty years, African American Appalachians have had to fight just to be noticed. This began when the first celebration of emancipation in America took place in the small town of Gallipolis Appalachia, on the Ohio River on September 22nd, 1863.

What filled this gap in my knowledge was reading Crystal Wilkinson’s collection Perfect Black, in which she explores her identity of being poor and black in Appalachia. In the opening, aptly named poem, ‘Terrain’, she describes herself in relation to the area.

“I am plain brown bag, oak & twig, mud pies & gut-wrenching gospel in the throats of old tobacco brown men….. I toe-dive in all the rivers seeking the whole of me, scout virtual African terrain sifting through ancestral memories, but still I’m called back home through hymns sung by stout black women in large hats & flowered dresses….All roads lead me back across the waters of blood & breast milk, from ocean to river, to the lake, to the creek, to branch & stream, back to sweet rain, to the cold water in the glass I drink when I thirst to know where I belong.”

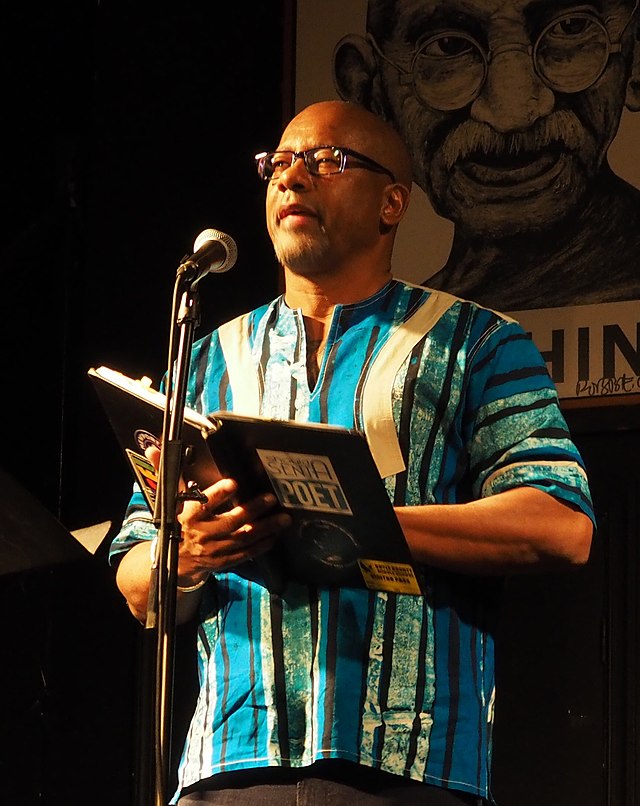

Wilkinson is part of a poetry collective known as The Affrilachian Poets. The term Affrilachia was coined by fellow poet, Frank X Walker in 1991 to address the gap in knowledge of the African American experience in Appalachia. In his own collection, Affrilachia, the poem Statues of Liberty, conveys the hard life of his mother. ‘mamma scrubbed/ rich white porcelain/ and hard wood floors/ on her hands and knees/ hid her pretty face and body/ in sack dresses/ and aunt jemima scarves/ from predators/ who assumed/ for a few extra dollars/ before Christmas/ in dark kitchen pantries/ they could/ unwrap her/ presents’

The collective has being going for over thirty years and celebrated its 25th anniversary with the anthology, Black Bone. Other poets in the collective include, Nikki Giovanni, and Bianca Spriggs, amongst others. Here is a Book Riot article on seven collections from the collective. Finally, if podcasts are your thing, there is a great series called Black in Appalachia.

Featured on Planet Poetry Podcast

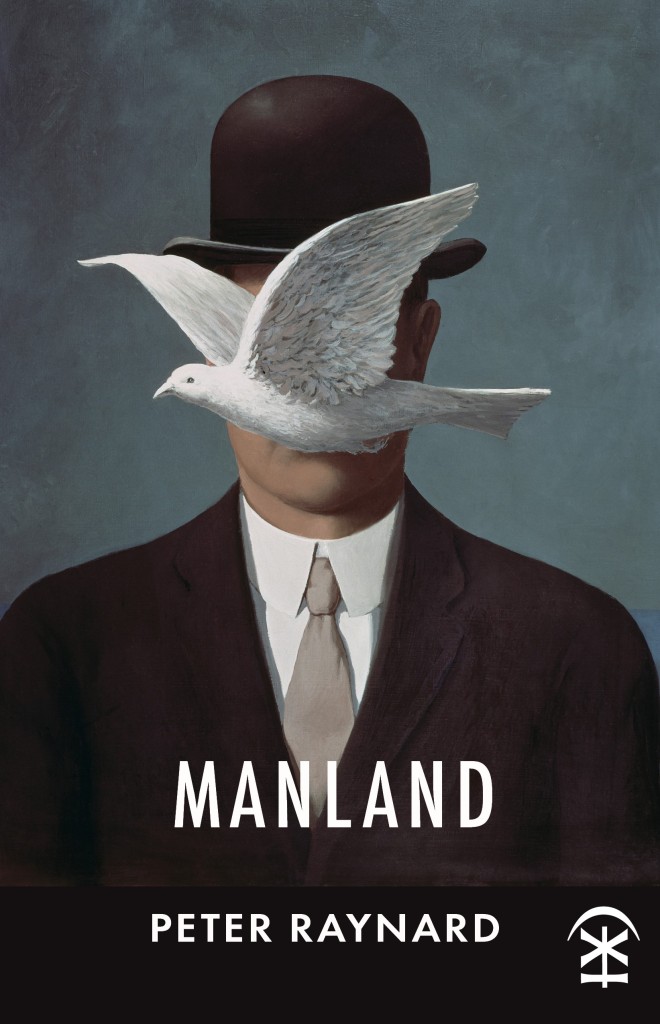

I had the great pleasure of talking about masculinity, class, disability and fatherhood with Peter Kenny and reading poems from my collection ‘Manland‘ on his and Robin Houghton‘s Planet Poetry Podcast. I hope you enjoy it.

Here is the link on Spotify:

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3S47nmrsdLCYQQMPvLrkQ8

If you don’t have Spotify you can listen to it on other platforms by going to,

https://planetpoetry.buzzsprout.com/

You can buy a copy of Manland from myself for £10 (incl. P&P UK only) or £13 (incl. P&P worldwide)

or direct from my publisher Nine Arches Press by clicking here

Featured Publication – Manland by Peter Raynard

My book Manland is the featured publication on Atrium. Thanks to Holly Magill and Claire Walker. You can get a copy here https://ninearchespress.com/publications/poetry-collections/manland

Our featured publication for September and October is Manland by Peter Raynard, published by Nine Arches Press.

Peter Raynard’sManlandis a bold, brilliant and outspoken new collection of poems that scrutinise men and manhood, mental health, working class lives and disability. Aloud and alive with music, wit, anger and rebellion, this is an accomplished, politically aware and vital book.

Raynard is a skilled observer, and these razor-sharp poems document parenthood through the lens of a stay-at-home dad, attempt to tell the truth about men and depression, study our cultural and social and medical relationships with drugs and drug-taking, and lay bare the realities of life at the sharpest edges of society. By turns frank, painful and bleakly funny, this humane and brilliant book encompasses pride and prejudices, the bonds between lads and dads, the toxic pressures of masculinity and the way illness and poverty irrevocably shape lives.

“InManlandPeter Raynard traverses…

View original post 362 more words

The Communist Manifesto: a poetic coupling by Peter Raynard

On the day of Marx’s birth, my poetic coupling of the Communist Manifesto

The following appeared on the brilliant Culture Matters site, edited by Mike Quille. The site is a great source and resource of working class and socialist culture.

A Poetic Coupling of the Communist Manifesto by Peter Raynard (with Karl Marx)

Counting in at around 12,000 words, can there be a more influential book with so relatively few words, than the Communist Manifesto? Today (21st February, 2018) is said to be the 170th anniversary of its publication. Written in a six-week rush, after the Communist League imposed a deadline on Marx, its take up has been phenomenal and its relevance remains today, if not more so.

Much is planned to mark the occasion, especially as it is also the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth on May 5th. I have read the Manifesto a number of times over the years. However, as a poet, I hadn’t given it…

View original post 1,105 more words

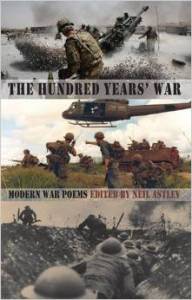

Book Review: The Hundred Years’ War: Modern War Poems edited by Neil Astley

Another reblog in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, from 2015 of a book of war poems published by Bloodaxe Books

‘There is nothing one man will not do to another.’ (The Visitor, Carolyn Forché)

‘There is nothing one man will not do to another.’ (The Visitor, Carolyn Forché)

On 7th January 1915 the war in Europe was at a stalemate. Soldiers were still dying for an unknown cause but the papers in the UK at least, were headlined with floods that covered much of the country. On the following day, the future UK Prime Minister David Lloyd George, in response to the war not ‘being over by Christmas’, said that half a million new volunteers should not be ‘thrown away in futile enterprises’ and by ‘this intermittent flinging …. against impregnable positions’.

‘Tumbling over hills, likes waves of the sea/Staggering on, attracted magnetically by Death.’ (At the Beginning of the War, Peter Baum, 1915)

View original post 654 more words

Postman in the Smoke, and Inferno by Antony Owen

I am republishing this post from 2015 by Antony Owen, as a mark of solidarity with the people of Ukraine.

When you look at the iconic picture taken of the German city of Dresden in 1945, it is as though the statue of the Rathausturm, known as ‘Die Gute’ (the Goodness – a personification of kindness), is pointing in disbelief at the utter devastation wrought by the British, where an estimated 25,000 people (many of them civilians) were killed. Almost five years previously in November 1940, my home town of Coventry, was heavily bombed by the Germans because of its industry and munitions factory. Although the death toll (estimated c560+) was far less than in Dresden, it was still massively devastating in terms of the damage done to the city, which took years to rebuild.

When you look at the iconic picture taken of the German city of Dresden in 1945, it is as though the statue of the Rathausturm, known as ‘Die Gute’ (the Goodness – a personification of kindness), is pointing in disbelief at the utter devastation wrought by the British, where an estimated 25,000 people (many of them civilians) were killed. Almost five years previously in November 1940, my home town of Coventry, was heavily bombed by the Germans because of its industry and munitions factory. Although the death toll (estimated c560+) was far less than in Dresden, it was still massively devastating in terms of the damage done to the city, which took years to rebuild.

The greatest symbol of that destruction is the ruins of the old Coventry Cathedral. I still go up its tower, St Michael’s, and two things stay with me when I look at the view; the…

The greatest symbol of that destruction is the ruins of the old Coventry Cathedral. I still go up its tower, St Michael’s, and two things stay with me when I look at the view; the…

View original post 685 more words

Dance Class by Hannah Lowe

Delighted that Hannah Lowe has won the overall Costa Book Award for her Bloodaxe Book, ‘Kids’. Here she is from 2015 with the poem ‘Dance Class’ taken from her 2013 collection ‘Chick’.

At fifteen I was a punk. I don’t have the spiky hair anymore (don’t have any in fact) but I still like to think I have a little bit of the ethos. My son is fifteen and into much the same type of alternative music, although his relates more to the various genres of heavy metal. It is only now, however, I have spotted a contradiction in our choices, for although I reveled in being different, I also wanted to be part of a group who looked and felt the same.

What we all have in common, whatever identity we feel we have, is the need to belong to something. It may only be with four other boys playing Warhammer in Games Workshop on a rainy Sunday afternoon, or as in Hannah Lowe’s poem Dance Class, being with ‘the best girls posed like poodles at a show‘. But it is often not that…

What we all have in common, whatever identity we feel we have, is the need to belong to something. It may only be with four other boys playing Warhammer in Games Workshop on a rainy Sunday afternoon, or as in Hannah Lowe’s poem Dance Class, being with ‘the best girls posed like poodles at a show‘. But it is often not that…

View original post 553 more words

Inside Out by Zeina Hashem Beck

This post from 2018 with poem by Zeina Hashem Beck about attacks on Gaza in 2014 shows the ongoing trauma Palestinian children grow up with.

The late great Liverpool football manager Bill Shankly had many famous sayings that are repeated to this day. The one that struck me growing up was, “Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.” Although I have followed football all my life, I have rarely, if ever  worn my team’s shirt. For one, I didn’t want to get beaten up by any wayward away fans; and two, I have never liked the tribal allegiance element of the game nor the violence that lies behind it.

worn my team’s shirt. For one, I didn’t want to get beaten up by any wayward away fans; and two, I have never liked the tribal allegiance element of the game nor the violence that lies behind it.

Football is also not devoid of influencing national politics to the point of igniting armed conflict as was the case in 1969 between Honduras and El Salvador. The political map influences where teams will play; most notable being that the Israeli…

View original post 567 more words

On This Day She

My original poetry mentor, the brilliant Jo Bell has co-wrote this important book of women’s lives.

On This Day She is the new book from Jo Bell, Tania Hershman and Ailsa Holland – a page-a-day history book featuring 366 women who have earned a place in history, but haven’t always got it. You can watch a recent event in which the three of us talked about the book and some of the women in it, here.

History is not just ‘what happened in the past.’ It is the story of what happened in the past. Our existing stories need an overhaul, because women have not been fairly represented in them. There are plenty of women who should have taken their place in any accounts of great deeds and cultural change. If they don’t appear in those accounts, that is not because they weren’t there.

Artists and philosophers are downplayed as the ‘muses’ of men for whom they were…

View original post 293 more words