Well the European Union is to lose a member. Maybe it will lose other members. Maybe it will be the end of the Union. What it won’t make a difference to (at least in positive terms), are the crises from Libya to Afghanistan that see thousands of refugees attempting to come to European shores. I am not going to get into the reasons for this fracture in European politics, which is as worrying at it has been since WW2. But one reason is not immigration. I don’t mean people didn’t vote with immigration as an issue, what I mean is that, whether there is an EU or not, it won’t make the slightest difference to these war torn people. And that is the shame of the referendum, which in my opinion should not have been undertaken. It was an ego trip of Cameron to have a legacy; well he’s got one now, but like Blair, it’s not the one he wanted.

Well the European Union is to lose a member. Maybe it will lose other members. Maybe it will be the end of the Union. What it won’t make a difference to (at least in positive terms), are the crises from Libya to Afghanistan that see thousands of refugees attempting to come to European shores. I am not going to get into the reasons for this fracture in European politics, which is as worrying at it has been since WW2. But one reason is not immigration. I don’t mean people didn’t vote with immigration as an issue, what I mean is that, whether there is an EU or not, it won’t make the slightest difference to these war torn people. And that is the shame of the referendum, which in my opinion should not have been undertaken. It was an ego trip of Cameron to have a legacy; well he’s got one now, but like Blair, it’s not the one he wanted.

Yes, the EU has failed the refugees, not least by paying off Turkey to keep them from making the journey. But that is not why people in the UK have voted to leave; setting aside the few on the Left, many of the others voted to Leave because they feel the EU has failed to keep these people out; that Britain can’t control its borders. If there is a problem, it is not with the numbers, it is more one of distribution; relatively large concentrations of refugees in a short space of time in small areas, without the necessary public services to help their integration. There should be a targeted investment in the community as a whole (both new and not-so-knew members); done in a way that doesn’t make people feel there is an unfair competition for services, whether for housing, jobs or school places. This is what we have done in the United Kingdom for many years. Not now. Not with an ideological austerity-driven government, who with tragic irony has managed to hand power to a small group of right wing demagogues.

The other sad irony of the decision to Leave is that the United Kingdom couldn’t be further away (in European terms) from the influx of large numbers of refugees. Added to this tragedy has been the fact that this has been left to the most crisis ridden country in Europe, Greece, to deal with it. Emer Davis shows us first-hand the situation facing Greece during this time in her poignant poem, Transient Lives. (Emer was selected as an asylum expert to assist the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) with the EU Relocation Programme on Lesvos Island). “Lesbos/Home to ouzo/And olive oil,/Cobbled lanes and wooden balconies,/The rambling stillness/Of the petrified forest,/Burnt skin trembling/Among dead trees,/We tremble in the evening sun/Re-telling the stories we heard,/And watch an old fisherman Bashing an octopus against a wall.” (more…)

The other sad irony of the decision to Leave is that the United Kingdom couldn’t be further away (in European terms) from the influx of large numbers of refugees. Added to this tragedy has been the fact that this has been left to the most crisis ridden country in Europe, Greece, to deal with it. Emer Davis shows us first-hand the situation facing Greece during this time in her poignant poem, Transient Lives. (Emer was selected as an asylum expert to assist the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) with the EU Relocation Programme on Lesvos Island). “Lesbos/Home to ouzo/And olive oil,/Cobbled lanes and wooden balconies,/The rambling stillness/Of the petrified forest,/Burnt skin trembling/Among dead trees,/We tremble in the evening sun/Re-telling the stories we heard,/And watch an old fisherman Bashing an octopus against a wall.” (more…)

At the birth of my first son, after a somewhat traumatic first week of his life, my father said to me, in his dry wit, “You’ve a lifetime of worry ahead of you. When you’re 80 and he’s 50, you’ll still feel the same.” Now my father is in his 80s, for me the worry works both ways, to my teenage sons as well as my parents. The greatest parental experience I have had is becoming a stay-at-home/househusband/underling of my two sons some eight years ago. I was brought front stage on the gender divide of parenting; evidenced at first hand the plates mothers are juggling, as many of my new plates smashed on the floor.

At the birth of my first son, after a somewhat traumatic first week of his life, my father said to me, in his dry wit, “You’ve a lifetime of worry ahead of you. When you’re 80 and he’s 50, you’ll still feel the same.” Now my father is in his 80s, for me the worry works both ways, to my teenage sons as well as my parents. The greatest parental experience I have had is becoming a stay-at-home/househusband/underling of my two sons some eight years ago. I was brought front stage on the gender divide of parenting; evidenced at first hand the plates mothers are juggling, as many of my new plates smashed on the floor. My father was one of them, and so was David Cooke’s, whose father opted for retirement in his very early fifties, and is the subject of his poem, “Work”. His father was “a ‘man’s man’ my mother said, who needed/a joke to keep him going, and something to get him up in the morning besides/a late stroll to place his bets at Coral.” As a young son or daughter, the roles of your parents are defined by their actions; of what they do, and in them days it was the father who was out all day at work. So when he is made redundant, he is lost. “I’d learn that no one’s indispensable./So after he’d botched a shed, dug the pond/and built a rockery, the time was ripe/for change.” They had worked all their lives and didn’t want to lay fallow on the dole. My own father went on to do different jobs, as did David’s who “With a clapped-out van and a mate,/he started again on small extensions.”

My father was one of them, and so was David Cooke’s, whose father opted for retirement in his very early fifties, and is the subject of his poem, “Work”. His father was “a ‘man’s man’ my mother said, who needed/a joke to keep him going, and something to get him up in the morning besides/a late stroll to place his bets at Coral.” As a young son or daughter, the roles of your parents are defined by their actions; of what they do, and in them days it was the father who was out all day at work. So when he is made redundant, he is lost. “I’d learn that no one’s indispensable./So after he’d botched a shed, dug the pond/and built a rockery, the time was ripe/for change.” They had worked all their lives and didn’t want to lay fallow on the dole. My own father went on to do different jobs, as did David’s who “With a clapped-out van and a mate,/he started again on small extensions.” As we slowly make our way to the voting booth for the EU referendum, what has struck me is

As we slowly make our way to the voting booth for the EU referendum, what has struck me is  Jasmine Ann Cooray’s poem, Ice-cream Box of Frozen Curry beautifully expresses this generational difference from her experience being of Sri Lankan and mixed European lineage. The poem conveys the journey of a newcomer to the country, the people they leave behind (“Dear village leavers/Dear fortune seekers/Dear don’t forget us/Dear whispered prayers”), and the new rules and racism the leavers experience (“Dear name,/Dear get to work/Dear roads and railways/Dear NHS/Dear filthy Paki/Dear bite your tongue”). This is an immense a coming-of-age/rights of passage story that is both funny and sad, matching the older generation (Dear ice-cream box of frozen curry/Dear tiny aunts with iron grip/Dear random portly shouting uncles/Dear grandma wince at dodgy hip) with the ways the younger generation try to create their own identity (Dear make-up practise after lights off/Dear boyfriend legs it out the back/Dear promise I was in the library/Dear shaving threading bleaching wax).

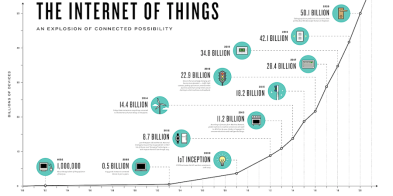

Jasmine Ann Cooray’s poem, Ice-cream Box of Frozen Curry beautifully expresses this generational difference from her experience being of Sri Lankan and mixed European lineage. The poem conveys the journey of a newcomer to the country, the people they leave behind (“Dear village leavers/Dear fortune seekers/Dear don’t forget us/Dear whispered prayers”), and the new rules and racism the leavers experience (“Dear name,/Dear get to work/Dear roads and railways/Dear NHS/Dear filthy Paki/Dear bite your tongue”). This is an immense a coming-of-age/rights of passage story that is both funny and sad, matching the older generation (Dear ice-cream box of frozen curry/Dear tiny aunts with iron grip/Dear random portly shouting uncles/Dear grandma wince at dodgy hip) with the ways the younger generation try to create their own identity (Dear make-up practise after lights off/Dear boyfriend legs it out the back/Dear promise I was in the library/Dear shaving threading bleaching wax).  In computing, Moore’s Law stated that the overall processing power of a computer would double every two years. This has literally powered the start of a wave of technological development, whose social impact is unfathomable, especially if we remember we are still the same cognitive creatures we were hundreds of years ago, when things changed at a far slower pace. This is both frightening and exciting and has accelerated the outcome of international capitalism – globalisation; that great sway of moving things, from people to pins.

In computing, Moore’s Law stated that the overall processing power of a computer would double every two years. This has literally powered the start of a wave of technological development, whose social impact is unfathomable, especially if we remember we are still the same cognitive creatures we were hundreds of years ago, when things changed at a far slower pace. This is both frightening and exciting and has accelerated the outcome of international capitalism – globalisation; that great sway of moving things, from people to pins. Mike Gallagher’s powerful poem, Paraic and Jack and John, tells a familiar story of the Irish diaspora, who have left to go to the UK, America and elsewhere, and the gap this left for those still living in Ireland. “not too many options there,/the bus up Gowlawám,/the train to Westland Row./Holyhead gave them choices:/Preston? Ormskirk? Cricklewood?” These men traversed the 260 mile long A5 road that runs from Holyhead on the Welsh island of Anglesey all the way to London and the Kilburn Road.

Mike Gallagher’s powerful poem, Paraic and Jack and John, tells a familiar story of the Irish diaspora, who have left to go to the UK, America and elsewhere, and the gap this left for those still living in Ireland. “not too many options there,/the bus up Gowlawám,/the train to Westland Row./Holyhead gave them choices:/Preston? Ormskirk? Cricklewood?” These men traversed the 260 mile long A5 road that runs from Holyhead on the Welsh island of Anglesey all the way to London and the Kilburn Road.