If working class was a currency in poetry, it wouldn’t be worth very much. For the past few years there has been a slow degradation of the working class experience; trailing behind novels, memoirs, plays, and photography. A catalogue of poetry books published in 2023 found class, along with work, a very minor subject in the minds of poets today. So it was a welcome surprise to review Jake Hawkey’s But & Though, published by Pan Macmillan.

Hawkey’s life began in the Thamesmead / Woolwich / Plumstead area of London, where if you were into football Charlton would be your team. Looking through the Table of Contents the titles indicate the environment we are about to inhabit. Poems such as ‘Fake Ransom Note’, ‘Dad’s still in a coma so I’m sent’, ‘Working Class Boy in a Shower Cap, and ‘Juliet Says to the Nurse the City is a Bruise’ all colour a life in three acts. From childhood to adulthood, this is no ordinary life in any sense of a germ free adolescence. If you’ve read Katriona O’Sullivan’s memoir Poor, you will know what I mean. The title is another clue, as But & Though is the language of addiction with all of its excuses, delaying tactics and unkept promises.

The first line of the book is, ‘I remember’, which is a poignant summation of something you would rather forget, for the opening poems are an elegy to his mother’s alcoholism and absence through the drink,

I was just a boy when mum was drunk

every night & I thought that meant

she did not love me. The unloved

still rents the rooms of my body.

and then the memories of his father’s coma:

When they run their final tests,

they pour water into his ear

like a closing plea of the sea

to wake him

In ‘Wrappers’ his younger brother deals with his father’s death by not leaving the flat and ordering Maccy D’s breakfast each day. The family is a freeze frame from the death. They stay home, where ‘the game shows of Saturday fend off the silence/ only deliveries open the door to sunlight.’

But there is love and tenderness within lines of the poems. ‘there’s Dad’s/ old phone with your number/ stored as both Boozy & Woozy/ Despite being dizzy he still/ loved and loves you.’ Similarly in ‘London & Sons’, Hawkey displays humorous word games in talking about his friends, ‘o emperors! / you are only / caesar salads.’

But make no mistake there is a permeating darkness in past memories and setting of family life following his father’s death. The narrator is central to the family sticking together, whether a child or not – the difference in age between mother and son shrinks and is upturned. So the child grows up before their time, missing many of the rites of passage other friends of his age go through.

Signals of poverty and fucked up priorities, are evident in a number of poems. Addressing his mother in ‘Sticks not Twigs’, small Ronnie/ doesn’t have money for football boots/ or training subs this week – / you don’t mind though, if there’s/ booze in the fridge, cigarettes in the house.’ Each family member has to play by these unwritten rules, and they should never share them to anybody outside the family circle.

What is the residue, the echo that such dysfunction has in the long term? Both physical and mental, we are exposed to the reality of a mother who tells her son that ‘I smoked and drank with you, with them in the womb.’ The possibility for the children of ‘Foetal alcohol spectrum disorder.’ The boy seeks out memories as a way to cope, ‘in exile I miss home, / the way Nanny P sweeps / through the TV guide / licking excess ink from her thumb.’

The second section is a bildungsroman of the boy becoming a man before his time. ‘In Boy Asking a Question’,

‘the boy asks what a boy asks

which is never

what a man looking back

would ask but only

what a boy would ask

& that’s okay.’

Within a single poem you see the boy mature, and question whether his father will be in heaven. Religion is a smoke alarm and his father being accepted by God as a good person, is what the boy wants to know. Are there still fires, even when he has gone.

There are some fizzing prose poems. In ‘Brahms & Liszt’ Hawkey further shows his role as family mediator between his sister, (‘who has come home ‘completely gazeboed from the clubhouse’) and his mother who wants to ‘tear off her head’.

Time and again, the ‘remembering’ (sometimes arising out of therapy) sits starkly in the present tense when describing the normality of dysfunction, and Hawkey’s insight here is heart breaking. ‘you forget the individual bombs, bullets or duds of a war stuck on a loop, where the truth is not the first casualty, it’s one’s reverence for the truth.’

Within this teenage passage, Hawkey writes a paean to his sister J (The Girl Who Grew Up to Drive Ambulances), which marries their lost childhood with her job as a paramedic.

‘These are you lights now

flashing blue over streets

where you kicked footballs

where your mother

drove you to school’

Ending playfully with a ribbing from her ambulance colleague who affectionately describes the origin of the word ‘silly’ which once meant holy, but came to mean righteous, to mean silly, to mean noble, innocent, harmless, helpless, ignorant, childish, goofy ‘absolute goof ball like you! she says’

The final Act of the book is both reflective through maturity, and forward looking to the possibility of starting a family of his own.

The title poem ‘But & Though’ evokes the friendship between his two sisters, ‘where ‘there’s never any news so they make their own’. Then, in the ironically titled ‘Happy Hour’ where the weight of letting go of someone you love, is for a long time all that he learned.

But there is much light shone in a number of poems, which ‘The Present’ is a standout example. It is the first ‘Jesus’s birthday’ where his mother isn’t slurring by 3pm but the wounds of her past are evident in her wheelchair. Hawkey, now a teacher references a student’s poem where a ‘briefcase left on a tube [is] finding a new life within the lost & found, department’ and as a poet brilliantly matches a Paul Gascoigne (Gazza) goal against Scotland with an act of Jesus on the cross, once more bringing Religion into the collection like a shadow, or reference point.

His mother is now nearing her end, as a granddaughter signals a different present tense, one where memories are not wounds but ones you cherish through the simple acts of creativity that a child can aspire to. Not something unachievable, but something both mundane and marvellous, as a life should be.

‘my love, somewhere in the world

a poet is sitting down to write;

a pastry sous chef is rubbing

sleep from an eye; one lover

is inking a hymn to another

just because it’s a Tuesday.’

I hesitate to name the collection a debut, not only because it brings connotations of the noble amateur, but because Hawkey has written a book about working class life that is worthy of any collection in a poet’s oeuvre.

There may be fewer portrayals of the working class in poetry than there once was, or ought to be, but like the closing passages of But & Though, this book brings hope that the canon is still alive, if not more than a little scarred from its past.

Copies of But & Though can be bought here

In novels and films, plays even, there are state-of-the-nation portrayals aplenty; from Dickens to

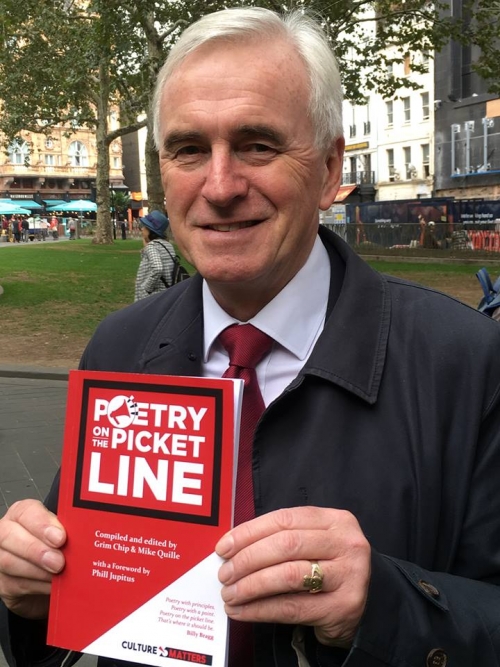

In novels and films, plays even, there are state-of-the-nation portrayals aplenty; from Dickens to  It’s been really hot at times this year – pushing into the 30s at times back in the summer. It’s been really cold at times this year – pushing into the minuses at times in the mornings. And yet, they are there, rain or shine, supporting the workers who are having to strike in order to either get proper working conditions or a living wage that they more than deserve. The heroes of Poetry on the Picket Line (PotPL) are the likes of

It’s been really hot at times this year – pushing into the 30s at times back in the summer. It’s been really cold at times this year – pushing into the minuses at times in the mornings. And yet, they are there, rain or shine, supporting the workers who are having to strike in order to either get proper working conditions or a living wage that they more than deserve. The heroes of Poetry on the Picket Line (PotPL) are the likes of  History is nothing without memory, memorials, and remembrances. And on such a day as this, the marking of the end of the First World War, there is a particular resonance to what it means today. As

History is nothing without memory, memorials, and remembrances. And on such a day as this, the marking of the end of the First World War, there is a particular resonance to what it means today. As  Is there enough anger in mainstream poetry today; in the journals/magazines and collections? In the US from

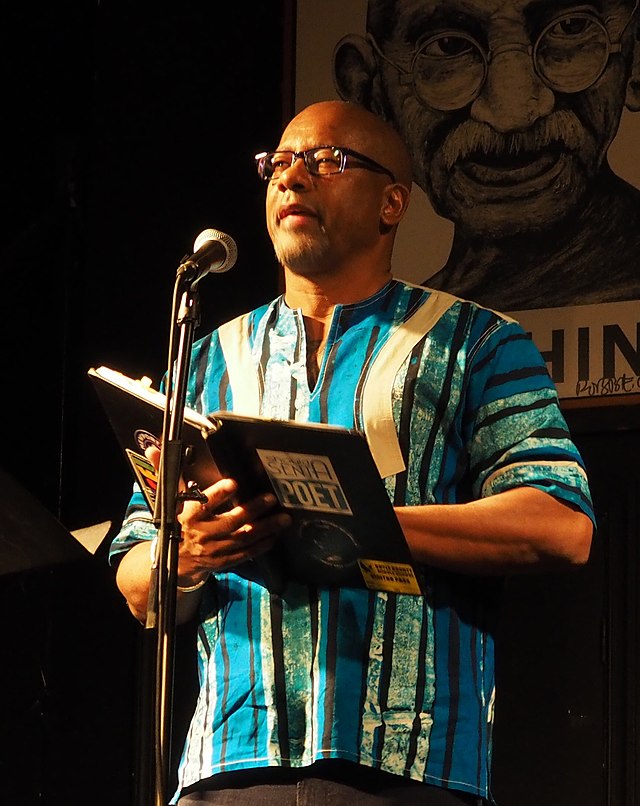

Is there enough anger in mainstream poetry today; in the journals/magazines and collections? In the US from  Fran Lock, who has appeared on this site a number of times, is, along with Melissa Lee Houghton, one of those electrifying poets both on the page and the stage. Since

Fran Lock, who has appeared on this site a number of times, is, along with Melissa Lee Houghton, one of those electrifying poets both on the page and the stage. Since  The second part of the collection is a wonderful grotesque imagining of a place called Rag Town and the girls who inhabit it, in particular the ubiquitous La La. In her notes on this section Fran says: “We have the right, and we deserve the space in which to be angry. I started writing the Rag Town sequence with this one thought looping endlessly in my head.” This was driven by Fran’s disillusion with what International Women’s Day has become; originally called International Working Women’s Day, the dropping of the ‘Working’ de-classed the day, so that in Fran’s words it has become divisive to raise issues of class as they relate to women’s oppression. “It’s divisive, for example, to say that white, settled, middle-class women “escape” from unlovable and undervalued domestic labour at the expense of working-class women, immigrant women, women in poverty.”

The second part of the collection is a wonderful grotesque imagining of a place called Rag Town and the girls who inhabit it, in particular the ubiquitous La La. In her notes on this section Fran says: “We have the right, and we deserve the space in which to be angry. I started writing the Rag Town sequence with this one thought looping endlessly in my head.” This was driven by Fran’s disillusion with what International Women’s Day has become; originally called International Working Women’s Day, the dropping of the ‘Working’ de-classed the day, so that in Fran’s words it has become divisive to raise issues of class as they relate to women’s oppression. “It’s divisive, for example, to say that white, settled, middle-class women “escape” from unlovable and undervalued domestic labour at the expense of working-class women, immigrant women, women in poverty.”