Deference. That key ingredient for soft power, even if it is enforced by hard methods (think of Putin or Trump). A lot would argue that deference is in decline. Figures on trust in public individuals, such as politicians, but also the media, are in decline. The internet allows for a greater challenge to authority than ever before (notwithstanding the ongoing battle over who controls it). Still, I think deference has a lot to answer for when it comes to injustices meted out by those who hold power.

When the archaeology of child abuse is finally dug up, a lot of what was allowed to go on, could be put down to deference. When I was at school, I was once hit on the head with a toffee hammer by a PE teacher for suggesting we play football instead of rugby for a change (this was a Hogwarts type grammar school, that allowed a few of the likes of us in). He cut my head and left a large lump. But I never thought to report it to anybody (not even my parents) because given the regime, I didn’t feel anyone would believe me. But this is such a minor example, given what is now being uncovered in other schools, churches, and institutions where children are under the tutelage of adults (scouts, football). Trust and deference go together.

In the past there were never the type of safeguards that are in place now. An authority figure, be they a priest, teacher, or coach, would command a level of trust given the position they held. But challenging that position, especially when your own values (e.g. religious) are invested in such people, meant that many were afraid to speak out. I know this from the experience of my local community growing up where the priest was a paedophile. Today, many of those parishioners can no longer look at photos of the happiest days of their lives (weddings, christenings, confirmation) because he is in the picture.

It seems there are never ending examples still emerging; in just the past week I have read reports of alleged abuse of children at a ‘therapeutic’ Christian farm in the US state of Georgia, and the discovery of mass graves of young children by unwed mothers in Tuam, Ireland. Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s haunting but beautifully written poem, At Letterfrack is an account of similar abuse at the Industrial School in Ireland that went back to the 1930s. It was so bad that boys would try to escape. “Ice grows on dormitory windows. Inside, rows of snores./Together, two boys whisper and dress in the dark. Hand in hand,/they run through white fields towards home.” But as the Ryan Report found, “they would usually be apprehended, sometimes by local people, and returned to the school.” On return, “they are beaten and sprayed with a hose.” One can hardly imagine how the perpetrators could defend such treatment. But people have great belief in the Faith and the institution of the Church; this trust is passed onto those who represent it, and were thus rarely challenged or questioned about their cruel practices.

It seems there are never ending examples still emerging; in just the past week I have read reports of alleged abuse of children at a ‘therapeutic’ Christian farm in the US state of Georgia, and the discovery of mass graves of young children by unwed mothers in Tuam, Ireland. Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s haunting but beautifully written poem, At Letterfrack is an account of similar abuse at the Industrial School in Ireland that went back to the 1930s. It was so bad that boys would try to escape. “Ice grows on dormitory windows. Inside, rows of snores./Together, two boys whisper and dress in the dark. Hand in hand,/they run through white fields towards home.” But as the Ryan Report found, “they would usually be apprehended, sometimes by local people, and returned to the school.” On return, “they are beaten and sprayed with a hose.” One can hardly imagine how the perpetrators could defend such treatment. But people have great belief in the Faith and the institution of the Church; this trust is passed onto those who represent it, and were thus rarely challenged or questioned about their cruel practices.

Doireann Ní Ghríofa is a bilingual writer working both in Irish and English. Among her awards are the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature, the Michael Hartnett Prize, and the Ireland Chair of Poetry bursary. Her most recent book is ‘Oighear’. www.doireannnighriofa.com

At Letterfrack

From the Ryan Report on Industrial School Abuse, Volume 1,

Chapter 8, paragraph 162: “The children would run away at night

but they would usually be apprehended, sometimes by local people,

and returned to the school soon after.”

I

This bog of flattened bracken was once a vast forest,

filled with wildcats and wolves.

The bog still dreams of trees, buried deep, unseen.

II

Centuries ago, people build tougher roads here —

slats of wide wood hauled up and laid side by side

so treacherous wetlands of bog could be crossed.

These roads remain, far below the surfaced,

where years of peat grow over the past like scabs.

The bog swallows people and their paths.

The bog swallows itself.

III

Later, few trees grow

so people hunt the wood that lies below,

trunks of sunken forests buried in the bog.

At dawn, they seek patches of peat

where dew has disappeared, then pierce

the surface and push long rods deep,

deeper, through gulping ground

until they strike solid wood.

They pull chunks up and make rafters,

doorways, window frames.

From this land, a school and a spire rose.

IV

Behind the school, a path ends at a small gate–

small plot, small stones, where smalls letters spell small names.

Leaves whisper: there is nothing here to fear.

The earth holds small skulls like seeds.

V

Winter.

Ice grows on dormitory windows. Inside, rows of snores.

Together, two boys whisper and dress in the dark. Hand in hand,

they run through white fields towards home.

Does the land betray them?

No, a wizened hawthorn holds out hands to try to hide them.

VI

In winter, runaways are easily found. Even in the dark,

small bootprints break through white to the ground below.

Does the land betray them?

Yes, it shows their path through snow.

VII

They do not cry as they are dragged back, stripped of clothes,

pushed against the wall, their small feet sinking into snow.

There, they are beaten and sprayed with a hose.

Does the land protect them?

Yes, it holds their hands in the dark?

VIII

In dormitories of sleeping boys, they shiver and bleed

and weep black bogwater tears. Overhead, rafters dream

of their sunken mothers, submerged still,

deep in the bog.

Does the land protect them?

Yes, it stays under their fingernails forever.

IX

By March, the snow has returned to air, the footprints

disappeared. From the earth, buds open white petals to light

where wood anemones fill bog-paths with stars.

Do they hold onto this land?

No, they forget. They let go.

X

They boys grow up. They walk away.

They leave Letterfrack, and go to London, Dublin, Boston.

Through their dreams, the mountain cuts a stark shadow.

Do they hold onto this land?

Yes, it holds them hard always – as a scar silvers from a red welt,

it tightens at the throat like the notch of a belt.

At Letterfrack is from Doireann’s collection Clasp, published by Dedalus Press

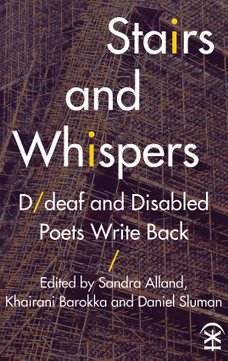

This was the launch of the anthology of “D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back”, edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka and Daniel Sluman, and published by Nine Arches Press. From the perspective of someone whose hearing and sight is not particularly impaired the event was a multi-media experience of poetry films, readings, and questions, supported by sign, subtitles, and the full text of poems. The editors described themselves for those with sight impairment, and in a large hall it felt like the most intimate and captivating experience.

This was the launch of the anthology of “D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back”, edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka and Daniel Sluman, and published by Nine Arches Press. From the perspective of someone whose hearing and sight is not particularly impaired the event was a multi-media experience of poetry films, readings, and questions, supported by sign, subtitles, and the full text of poems. The editors described themselves for those with sight impairment, and in a large hall it felt like the most intimate and captivating experience. Back home in one of the bars in my local, there was no women’s toilet (this was the mid-80s). The few women who did frequent the smoke room, had to go outside, in all kinds of weather, to the single female toilet in the other bar. At the same time an old school down the road still had signs showing the separate boys’ and girls’ entrances. Society remains divided in many ways, not only in gender. One of the most obvious, yet at the same time, nefarious, regards consumer preference.

Back home in one of the bars in my local, there was no women’s toilet (this was the mid-80s). The few women who did frequent the smoke room, had to go outside, in all kinds of weather, to the single female toilet in the other bar. At the same time an old school down the road still had signs showing the separate boys’ and girls’ entrances. Society remains divided in many ways, not only in gender. One of the most obvious, yet at the same time, nefarious, regards consumer preference. What do you think of when you think of home? Is it the history of wallpaper that reflects the changing times? The leather three-piece suite you bought off some bloke in the pub and had to drive down long country lanes to a hidden away warehouse – but was assured it was all totally legit? (I know someone who actually bought his house from someone in the pub). Was it the smell of chip fat in the kitchen as it cools back to white, a cracked window that was never fixed, the gradual wearing away of the staircase carpet?

What do you think of when you think of home? Is it the history of wallpaper that reflects the changing times? The leather three-piece suite you bought off some bloke in the pub and had to drive down long country lanes to a hidden away warehouse – but was assured it was all totally legit? (I know someone who actually bought his house from someone in the pub). Was it the smell of chip fat in the kitchen as it cools back to white, a cracked window that was never fixed, the gradual wearing away of the staircase carpet? Lorraine Carey’s beautifully evocative poem, From Doll House Windows, is about a childhood home and the memories it still holds. “An aubergine bucket served as a toilet,/in a two foot space. Mother cursed all winter/from doll house windows where we watched/somersaulting snowflakes.” And like the poem, many of us had a pet (mine was a succession of goldfish from the fair, that usually died after two weeks), “My father brought back a storm petrel/from a trawler trip. /I homed him in a remnant of rolled up carpet -/ that matched his plumage.” But in the chaos of a young family’s house, something dark goes beyond the everyday in Lorraine’s poem; a memory of home, which will never be forgotten.

Lorraine Carey’s beautifully evocative poem, From Doll House Windows, is about a childhood home and the memories it still holds. “An aubergine bucket served as a toilet,/in a two foot space. Mother cursed all winter/from doll house windows where we watched/somersaulting snowflakes.” And like the poem, many of us had a pet (mine was a succession of goldfish from the fair, that usually died after two weeks), “My father brought back a storm petrel/from a trawler trip. /I homed him in a remnant of rolled up carpet -/ that matched his plumage.” But in the chaos of a young family’s house, something dark goes beyond the everyday in Lorraine’s poem; a memory of home, which will never be forgotten. Aged sixteen, in my first (and only) year, as an apprentice at the General Electric Company, I went round the factory and sat with various workers for half a day each, to get to know what they did. One woman’s job involved, picking up a piece of component, putting it on small press, then pulling a lever to fit it. It took her less than two seconds to do one. When she had done about five, she said to me, “that’s it, love. That’s what I do.” This left ten seconds less than four hours to spend together, in which we had a good natter, and I learned a lot that had nothing to do with her job. Of course, it is only in looking back that I realised it was my first encounter in how society is diced and sliced in terms of gender and work, with the women as the army corps and the men as corporals (charge hands), sergeants (foreman), captains (manager), etc..

Aged sixteen, in my first (and only) year, as an apprentice at the General Electric Company, I went round the factory and sat with various workers for half a day each, to get to know what they did. One woman’s job involved, picking up a piece of component, putting it on small press, then pulling a lever to fit it. It took her less than two seconds to do one. When she had done about five, she said to me, “that’s it, love. That’s what I do.” This left ten seconds less than four hours to spend together, in which we had a good natter, and I learned a lot that had nothing to do with her job. Of course, it is only in looking back that I realised it was my first encounter in how society is diced and sliced in terms of gender and work, with the women as the army corps and the men as corporals (charge hands), sergeants (foreman), captains (manager), etc.. industrial febrile temperature rising across the country at that time (the poet Anna Robinson previously wrote about an aspect of this on the site, in her poems

industrial febrile temperature rising across the country at that time (the poet Anna Robinson previously wrote about an aspect of this on the site, in her poems  Lemn Sissay’s poem, “Spark Catchers”, is a tribute to the Matchwomen and is a physical landmark at the Olympic Park where the factory was located. The poem is also an inspiration for an upcoming musical piece composed by Hannah Kendall and performed by the UK’s first black and ethnic minority orchestra, Chineke, at the

Lemn Sissay’s poem, “Spark Catchers”, is a tribute to the Matchwomen and is a physical landmark at the Olympic Park where the factory was located. The poem is also an inspiration for an upcoming musical piece composed by Hannah Kendall and performed by the UK’s first black and ethnic minority orchestra, Chineke, at the

Ben Banyard’s poem ‘This is Not Your Beautiful Game’ nicely captures the reality and sometime excitement of such wind-blown support, “This is not Wembley or the Emirates./We’re broken cement terraces, rusting corrugated sheds,/remnants of barbed wire, crackling tannoy.” You don’t get prawn sandwiches here (not that you would want them), it’s “pies described only as ‘meat’,/cups of Bovril, instant coffee, stewed tea.” But out of such masochistic adversity, comes great strength, as well as pride. “Little boys who support our club learn early/how to handle defeat and disappointment…./We are the English dream, the proud underdog/twitching hind legs in its sleep.” It is never too late for some players’ dreams; many have risen out of the lower ranks, to play in the Premier League, like Chris Smalling, Charlie Austin, Jimmy Bullard, Troy Deeney, and Jamie Vardy. And of course not forgetting Coventry’s own Trevor Peake, who at the age of 26 was bought from Lincoln City and was part of the 1987 FA Cup winning side.

Ben Banyard’s poem ‘This is Not Your Beautiful Game’ nicely captures the reality and sometime excitement of such wind-blown support, “This is not Wembley or the Emirates./We’re broken cement terraces, rusting corrugated sheds,/remnants of barbed wire, crackling tannoy.” You don’t get prawn sandwiches here (not that you would want them), it’s “pies described only as ‘meat’,/cups of Bovril, instant coffee, stewed tea.” But out of such masochistic adversity, comes great strength, as well as pride. “Little boys who support our club learn early/how to handle defeat and disappointment…./We are the English dream, the proud underdog/twitching hind legs in its sleep.” It is never too late for some players’ dreams; many have risen out of the lower ranks, to play in the Premier League, like Chris Smalling, Charlie Austin, Jimmy Bullard, Troy Deeney, and Jamie Vardy. And of course not forgetting Coventry’s own Trevor Peake, who at the age of 26 was bought from Lincoln City and was part of the 1987 FA Cup winning side.

Julia Webb’s poignant (and wonderfully titled) poem ‘because my home town has a hand between its legs’, encapsulates this precarious, exciting, and frightening time from the perspective of girls/young women, “we spend too much time in public toilets – /smoking, scratching boy’s names onto cubicle doors,/rolling clear lip gloss onto kissable lips.” We all remember hanging out on the streets, when there may have not been a youth club, and the pubs were beyond reach. “Spaces find you: the concrete slope under the road bridge,/the shadowy space beneath the walkways at the bottom of the flats.” And sadly, the vulnerability and dangers that one can be open to, “make sure your Mum’s friend never gives you a ride home alone.”

Julia Webb’s poignant (and wonderfully titled) poem ‘because my home town has a hand between its legs’, encapsulates this precarious, exciting, and frightening time from the perspective of girls/young women, “we spend too much time in public toilets – /smoking, scratching boy’s names onto cubicle doors,/rolling clear lip gloss onto kissable lips.” We all remember hanging out on the streets, when there may have not been a youth club, and the pubs were beyond reach. “Spaces find you: the concrete slope under the road bridge,/the shadowy space beneath the walkways at the bottom of the flats.” And sadly, the vulnerability and dangers that one can be open to, “make sure your Mum’s friend never gives you a ride home alone.” It seems there are never ending examples still emerging; in just the past week I have read reports of alleged abuse of children at

It seems there are never ending examples still emerging; in just the past week I have read reports of alleged abuse of children at

Catherine Graham’s poem Market Scene, Northern Town evokes this scene of bustling activity and its mix of goods: “The lidded stalls are laden with everything/from home-made cakes to hand-me-downs.” This is a tradition that is woven into daily activities: “They’ve/spilled out from early morning mass,/freshly blessed and raring to bag a bargain,/scudding across the cobbles, like shipyard workers/knocking off.” And from the food bought, you will “smell the pearl barley,/carrots, potatoes and onions, the stock bubbling/nicely in the pot.” We shouldn’t be too doom laden when it comes to the decline in markets, because they haven’t died out altogether, and I’m not sure they will. I for one would miss the market trader shouting, ‘Come ‘an ‘av a look. Pand a bowl!’

Catherine Graham’s poem Market Scene, Northern Town evokes this scene of bustling activity and its mix of goods: “The lidded stalls are laden with everything/from home-made cakes to hand-me-downs.” This is a tradition that is woven into daily activities: “They’ve/spilled out from early morning mass,/freshly blessed and raring to bag a bargain,/scudding across the cobbles, like shipyard workers/knocking off.” And from the food bought, you will “smell the pearl barley,/carrots, potatoes and onions, the stock bubbling/nicely in the pot.” We shouldn’t be too doom laden when it comes to the decline in markets, because they haven’t died out altogether, and I’m not sure they will. I for one would miss the market trader shouting, ‘Come ‘an ‘av a look. Pand a bowl!’ Let’s start with a joke: “There’s a black fella, a Pakistani, and a Jew in a nightclub. What a fine example of an integrated community.” Here’s another one for ya, “Two homosexuals in the back of a van, having sex. They’re over twenty-one! What’s wrong with that?” These are the anti-stereotype jokes of

Let’s start with a joke: “There’s a black fella, a Pakistani, and a Jew in a nightclub. What a fine example of an integrated community.” Here’s another one for ya, “Two homosexuals in the back of a van, having sex. They’re over twenty-one! What’s wrong with that?” These are the anti-stereotype jokes of  If this site does one thing, I hope it shows that the working class are not a one dimensional, culturally barren, single type of person. Poems from

If this site does one thing, I hope it shows that the working class are not a one dimensional, culturally barren, single type of person. Poems from