The following was recently published on Queen Mobs Tea House.

How to Write the Working Classes by Peter Raynard

(somewhat after Binyavanga Wainaina)

The collective noun for the working classes is ‘These People’, never ‘The People’ or ‘My People’; use of the latter terms will get you the sack for empathetic tendencies. Terms such as rank and file or blue collar are too political, whilst plebeians and proletariat outdated. Chavs has become common parlance, but only use that term to show how they are described by others. Try to maintain objectivity in this regard, as ridiculously hard as that may be.

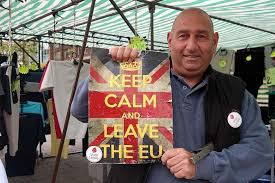

It is essential to make the reader believe there is but one type of working class person; they can be of a different age but they must look related, ideally inbred. The main type will be a saggy clothed, got a loyalty card from Sports Direct, Union Jack pale-faced male who claims he can trace his ancestors back to Neanderthal times, which in reality is just before the Second World War when his great granddad ran off with a Polish woman – but don’t talk about that obviously. Always have them accompanied by a muscle shaped dog, preferably tight-leashed, with a 70s punk rock sell-out dog collar, white drooling jaw, and a ravenous appetite for the calf-muscle of an outsider, which is basically anyone born within a mile of their ends.

It is essential to make the reader believe there is but one type of working class person; they can be of a different age but they must look related, ideally inbred. The main type will be a saggy clothed, got a loyalty card from Sports Direct, Union Jack pale-faced male who claims he can trace his ancestors back to Neanderthal times, which in reality is just before the Second World War when his great granddad ran off with a Polish woman – but don’t talk about that obviously. Always have them accompanied by a muscle shaped dog, preferably tight-leashed, with a 70s punk rock sell-out dog collar, white drooling jaw, and a ravenous appetite for the calf-muscle of an outsider, which is basically anyone born within a mile of their ends.

With females, try to find a young heavily made up woman in her late teens, early twenties at most, with a neck tattoo and a ciggie hanging from her botoxed lips. She must be pushing a pram, if possible with a brown skinned baby inside wailing its lungs out. Even better if she also has slightly older offspring biting at her heels.

With females, try to find a young heavily made up woman in her late teens, early twenties at most, with a neck tattoo and a ciggie hanging from her botoxed lips. She must be pushing a pram, if possible with a brown skinned baby inside wailing its lungs out. Even better if she also has slightly older offspring biting at her heels.

When trying to find one of them to interview, go to a Saturday market on a rainy day where the salt-of-the-earth traders shout ‘cum an’ ‘av a look, pand a bowl’ or similar sounding unintelligible whooping noises, in order to get you to buy their rotting fruit and veg. When approaching them try to speak in their tongue by swearing and commenting on the weather. Begin with the question, ‘how’s business?’ which actually means much more than in the literal sense. That is your ‘in’. Then go onto questions like, ‘do you think there are too many immigrants living in your back garden?’ or ‘how would you feel if your daughter came home with a Caribbean man who claimed he was a rapper?’ Similarly you could ask how they would feel about their son coming home with a gay bloke, who happens to be ‘a coloured’, and is a lawyer or a doctor. Get the camera man to zoom into their yellow teeth as they speak, then pan down to the blue blur of tattoos that sail across their wrinkled forearms, which they got when drunk at sea.

Once you’ve ‘got them’, ask if you could have a look at where they live. This will not only give you a cheap entry but also a safe one. Tell them that you come from a working class estate yourself and that you often go back to visit your withering ancestors. When describing the environment make sure adjectives like concrete, boarded up, brutal, dank, bleak, pepper your sentences like a well-seasoned steak. Highlight the fact that pie and mash shops are all but extinct, although their cultural appropriation is in train from bearded hipsters.

Get them to heap blame on the metropolitan elites (like yourself), who they feel rule over them like hand-me-down warlords from Henry the VIII; politicians will be the main target, but feel free to engage them in wider diatribes against big business, estate agents, and middle-class teachers who try to get their children to learn foreign languages.

However, never, ever bring the Royal Family into this part of the conversation. Reserve that for when you move them into nostalgia, about how life was much better in the good  old medieval days, even though many of them died before the age of five and none of the adults had their own teeth; why do you think they like soup so much? Then move on to Brexit and listen to the range of opinions on this newly found independence, from ‘we can now take our country back’ to ‘we can now send them back’. Pretend to take copious notes at this point to induce a feeling they are finally being listened to.

old medieval days, even though many of them died before the age of five and none of the adults had their own teeth; why do you think they like soup so much? Then move on to Brexit and listen to the range of opinions on this newly found independence, from ‘we can now take our country back’ to ‘we can now send them back’. Pretend to take copious notes at this point to induce a feeling they are finally being listened to.

Ask them about any problems with the estate but direct it towards people; e.g. where five or so years ago you may have inquired about a paedophile problem or the prevalence of ASBO kids, your focus must now be on Muslims, or people with an Arab or South Asian appearance, however vague. Get them to use their senses to describe the stink of the immigrants’ food; then go on to ask them what their favourite meal is when they’ve been out for a gallon of pints with mates – if you’re lucky they’ll say a ruby murray and bingo you’ve got them on the contradiction train. Talk also about the noise from the immigrant’s string-whiny music and the wailing from the wild amount of kids they have. They’ll probably go onto to how these families jumped the queue to get their council house in which they cram so many generations, some have to live behind the wallpaper.

Never refer to any musical or other cultural interests they may have themselves, although it will be very surprising if you found such interests. The only exception will be if they know someone’s second cousin removed who got to the regional semi-finals of Britain’s Got Talent with their rendition of God Save the Queen whistled entirely through their left nostril (the other one will have a ring through it). Of course, they may talk about their pigeons or how they collect Nazi memorabilia, but don’t pursue this because you’ll end up in some rotting smelly shed, being offered a roll up and a mug of quarry brown tea.

Finally, before leaving, slip a score (that’s a twenty btw) into the palm of their hand like a Priest’s Vaticum bread, give ‘em a wink, and say it’s been real. Rush off home to submit copy and then furiously shower yourself as if you’ve just been raped.

This sets aside the history they have lived through and the people they became because of it; a World War to monumental technological change from the TV to virtual reality. They have so many stories to tell and be told, and Beth McDonough’s eponymous poem ‘St Fergus Gran’ does just that. “Great Gran lived in weighty old pennies, dropped/from bonehard hands to my fat-cup palm/just before we’d journey west.” Like many stories, hers is one that is handed down the generations, “I never knew of her second sight/All those deaths, and how she kent/her brother lived, when the telegram said not.” Their lives weren’t a straightforward one of getting married and having children; war put pay to that. “I met the East End Glasgow lad she’d/fostered in the war, with all his tricks, his walk/to her from the west coast up to Buchan.” Here Beth tells us a little more about the poem:

This sets aside the history they have lived through and the people they became because of it; a World War to monumental technological change from the TV to virtual reality. They have so many stories to tell and be told, and Beth McDonough’s eponymous poem ‘St Fergus Gran’ does just that. “Great Gran lived in weighty old pennies, dropped/from bonehard hands to my fat-cup palm/just before we’d journey west.” Like many stories, hers is one that is handed down the generations, “I never knew of her second sight/All those deaths, and how she kent/her brother lived, when the telegram said not.” Their lives weren’t a straightforward one of getting married and having children; war put pay to that. “I met the East End Glasgow lad she’d/fostered in the war, with all his tricks, his walk/to her from the west coast up to Buchan.” Here Beth tells us a little more about the poem: therefore have very different connotations. Our poet today, Professor Aisha K. Gill [

therefore have very different connotations. Our poet today, Professor Aisha K. Gill [ In more wealthy countries people are also pressured to move. For example, because of past policies of selling off council housing,

In more wealthy countries people are also pressured to move. For example, because of past policies of selling off council housing,  Nonetheless, whether a refugee who has left their country, or internally displaced person, the majority of people still call home the place they were born. Joe Horgan’s poem, “The Maps You Took With You When You Went,” tells of the place he was born, Birmingham and the situation facing many working class people during the 1980s. The irony being that many came to the city, as they did to my own home of Coventry, from Ireland and Scotland, only to see a number of their own children leave; some went back to Ireland during the Celtic Tiger bubble, whilst others dispersed to various corners of the country and abroad.

Nonetheless, whether a refugee who has left their country, or internally displaced person, the majority of people still call home the place they were born. Joe Horgan’s poem, “The Maps You Took With You When You Went,” tells of the place he was born, Birmingham and the situation facing many working class people during the 1980s. The irony being that many came to the city, as they did to my own home of Coventry, from Ireland and Scotland, only to see a number of their own children leave; some went back to Ireland during the Celtic Tiger bubble, whilst others dispersed to various corners of the country and abroad.  I know that saying children are remarkable, is not a particularly remarkable thing to say. Nonetheless, I see it with my own sons; how they shrug off an argument they may have had, or in my older son’s case, how he recovered from severe depression. And I was reminded of this when seeing young boys smiling as they jumped into a water filled bomb crater, a splash pool of war, in Aleppo.

I know that saying children are remarkable, is not a particularly remarkable thing to say. Nonetheless, I see it with my own sons; how they shrug off an argument they may have had, or in my older son’s case, how he recovered from severe depression. And I was reminded of this when seeing young boys smiling as they jumped into a water filled bomb crater, a splash pool of war, in Aleppo. advancement in technology and so called smart bombs, civilian casualties are always much greater in the type of modern warfare we see in Syria.

advancement in technology and so called smart bombs, civilian casualties are always much greater in the type of modern warfare we see in Syria.  Reuben Woolley’s poem ‘all fall down’ poignantly captures the tragedy of war, “where/children sang in cinders”. As Michael Rosen did previously in his poem, ‘

Reuben Woolley’s poem ‘all fall down’ poignantly captures the tragedy of war, “where/children sang in cinders”. As Michael Rosen did previously in his poem, ‘ Power is ubiquitous and multi-layered. Just look at the range of power lists; from political figures, to those in the media,

Power is ubiquitous and multi-layered. Just look at the range of power lists; from political figures, to those in the media,  As individuals, it is quite easy for us to feel powerless and Hilda Sheehan’s poem The Speaker forcefully captures this sense through the metaphor of noise. “The Speaker//is an electric vulture//….It is/a god of dropped insects/from a carriage clock/or wasp holder/left to go on-off, on-off/riddling the town’s ears/from where it came.” This barrage of messages – part of this idea of influence, of soft power – is now at a ‘volume’ we cannot control. “Inside a speaker is Hell -/a radio of church-like/persuasion/from four walls a prison/of persecutors of/television visions/crackling away in the gutters.” It is not that easy to turn things off. But this powerless feeling of not being listened to is what brings people together; we see it with Black Lives Matter, with the Occupy movement, and the Arab Spring protests. There is both a soft and hard power that individuals can exert. One that is more than just a nudge to those in power. One that is a shout so loud it cannot be ignored.

As individuals, it is quite easy for us to feel powerless and Hilda Sheehan’s poem The Speaker forcefully captures this sense through the metaphor of noise. “The Speaker//is an electric vulture//….It is/a god of dropped insects/from a carriage clock/or wasp holder/left to go on-off, on-off/riddling the town’s ears/from where it came.” This barrage of messages – part of this idea of influence, of soft power – is now at a ‘volume’ we cannot control. “Inside a speaker is Hell -/a radio of church-like/persuasion/from four walls a prison/of persecutors of/television visions/crackling away in the gutters.” It is not that easy to turn things off. But this powerless feeling of not being listened to is what brings people together; we see it with Black Lives Matter, with the Occupy movement, and the Arab Spring protests. There is both a soft and hard power that individuals can exert. One that is more than just a nudge to those in power. One that is a shout so loud it cannot be ignored.  Like Father, like son. Well, when your father is Donald Trump, those footsteps should not be ones that you follow. But when nurture combines with nature, Junior treads where he has been fomented. DT Junior,

Like Father, like son. Well, when your father is Donald Trump, those footsteps should not be ones that you follow. But when nurture combines with nature, Junior treads where he has been fomented. DT Junior,  Those who came from another land, whether back in the day, or last week, are the currency of conversation and policy debate and inaction, at the present time. They are used in debates about Brexit, the war in Syria, lone terror attacks in the US, co-ordinated ones in Paris and Brussels. They are said to be the reason for Angela Merkel’s weak results in last week’s election in Germany,

Those who came from another land, whether back in the day, or last week, are the currency of conversation and policy debate and inaction, at the present time. They are used in debates about Brexit, the war in Syria, lone terror attacks in the US, co-ordinated ones in Paris and Brussels. They are said to be the reason for Angela Merkel’s weak results in last week’s election in Germany,  Matt Duggan’s poem “Voices from the Charcoal”, captures these fluid, turbulent and fateful times; “fishing boats once floating saviours for the persecuted/now we build walls from those we’ve liberated; /Cutting off our own ears /awakening a poisonous serpent for oil.” The powerful extract economically from other countries, through war for oil, then leave a mess that goes beyond the borders they originally set post-WW1. Matt reflects this marrying of history, “Those dusting jackboots are stomping/on the gravestones of our ancestors,/though we’d fill a whole lake with blood oil /we’d starve our own children leaving them to die on its banks.”

Matt Duggan’s poem “Voices from the Charcoal”, captures these fluid, turbulent and fateful times; “fishing boats once floating saviours for the persecuted/now we build walls from those we’ve liberated; /Cutting off our own ears /awakening a poisonous serpent for oil.” The powerful extract economically from other countries, through war for oil, then leave a mess that goes beyond the borders they originally set post-WW1. Matt reflects this marrying of history, “Those dusting jackboots are stomping/on the gravestones of our ancestors,/though we’d fill a whole lake with blood oil /we’d starve our own children leaving them to die on its banks.”  Hungry? No problem, look to the skies. Well, at the moment only if you’re a student at

Hungry? No problem, look to the skies. Well, at the moment only if you’re a student at  Poets have been aware of this, exposing the darker side of such developments.

Poets have been aware of this, exposing the darker side of such developments.  However, there are times when there needs to be protest even when the possibility of positive change has passed. A voice, or a mass of voices, coming together show the powerful in question that although they may have got away with it this time, a battle does not win a war. One of the most powerful forms of activism is marching. Marching comes in many guises outside of protest; from the obvious formation of armies going to battle, through to pipe bands. But as a form of protest the sight of hundreds of thousands of people, a great swathe of banners and heads pictured from above is a powerful image with a powerful message. Notable marches include

However, there are times when there needs to be protest even when the possibility of positive change has passed. A voice, or a mass of voices, coming together show the powerful in question that although they may have got away with it this time, a battle does not win a war. One of the most powerful forms of activism is marching. Marching comes in many guises outside of protest; from the obvious formation of armies going to battle, through to pipe bands. But as a form of protest the sight of hundreds of thousands of people, a great swathe of banners and heads pictured from above is a powerful image with a powerful message. Notable marches include  The UK has a long tradition of such marches, most notably the Jarrow March in 1936, in protest at unemployment and poverty in the North East. Previous to that was the mass trespass onto Kinder Scout in the Peak District, which is portrayed by the poet Peter Riley in his ‘

The UK has a long tradition of such marches, most notably the Jarrow March in 1936, in protest at unemployment and poverty in the North East. Previous to that was the mass trespass onto Kinder Scout in the Peak District, which is portrayed by the poet Peter Riley in his ‘ Leicester city.” But nonetheless they were successful in laying down a marker (in one case a physical one with the artwork of seven windows at Leicester’s St Mark’s Church, called

Leicester city.” But nonetheless they were successful in laying down a marker (in one case a physical one with the artwork of seven windows at Leicester’s St Mark’s Church, called