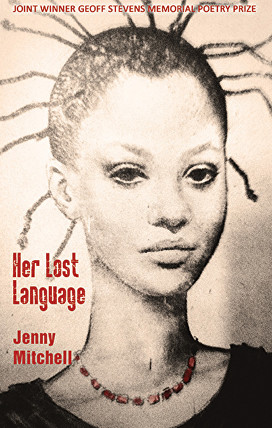

Today’s guest post is by Jenny Mitchell. Jenny was Joint winner of the Geoff Stevens Memorial Poetry Prize, run by Indigo Dreams Publishing, with her beautiful collection ‘Her Lost Language’. Paul McGrane of the Poetry Society, described the book as ‘a unique insight into a family history that invites you to re-imagine your own. I love this book and so will you!” You can buy a copy of the book here.

Jenny has given us the title poem from her book; a poignant depiction of life as a woman against a backdrop of terror and kidnap and the lack of refuge for those who escape.

*********************************

“The title poem for my debut collection, Her Lost Language, feels a bit like a ‘cuckoo’ in that I usually write about the legacies of British transatlantic enslavement, with direct reference to Jamaica. This seems to be where I find my voice, and can cover subjects from the maternal, food, past, present and future.

“The title poem for my debut collection, Her Lost Language, feels a bit like a ‘cuckoo’ in that I usually write about the legacies of British transatlantic enslavement, with direct reference to Jamaica. This seems to be where I find my voice, and can cover subjects from the maternal, food, past, present and future.

But the poem Her Lost Language was inspired by reports of Boko Haram in Nigeria, and their kidnapping/abuse/murder of girls and women, especially those seeking an education.

The articles about them seemed to coincide with more and more reports of a ‘hostile’ environment in the UK for immigrants and asylum-seekers.

I wanted to write about a woman who, having faced inhuman physical abuse, was being forced to endure the trauma of being ‘a stranger in a strange land’ that does not offer refuge.

I often write without knowing exactly what I mean but re-reading the poem I see that it’s very oral, lots about food and the sheer loneliness that can be symbolised in eating alone. I wonder if this is a metaphor for someone who cannot speak her language to anyone – a real language and an internal/emotional one – so ‘compensates’ by eating? Is she trying to cope by stuffing words down with food? Is cooking also a way to ‘recapture’ home?

It feels clear on re-reading the poem that the environment I describe is not just ‘hostile’ for the character but for everyone who has to live in it. The phrase, ‘A lift shaped by urine is’, to me, about real suffering – for those that have to endure it and those that cause the offence in the first place. How alienated do you have to be, to literally piss where you live?

It feels clear on re-reading the poem that the environment I describe is not just ‘hostile’ for the character but for everyone who has to live in it. The phrase, ‘A lift shaped by urine is’, to me, about real suffering – for those that have to endure it and those that cause the offence in the first place. How alienated do you have to be, to literally piss where you live?

The fact that the character has come from a place where the hills are shaped like God says something, to me, about what we have lost – ‘God’ as nature. Instead, the character in the poem looks for ‘God’ in a pastor who is remote, on television and instructing her to Give thanks when she lives and breathes suffering.

It’s always great to know what other people think so if you’d like to send your comments about this, or any of my poems, get in touch on Twitter @jennymitchellgo, or in the comments section below.”

Jenny Mitchell is joint winner of the Geoff Stevens’ Memorial Poetry Prize (Indigo Dreams Publishing). Her work has been broadcast on Radio 4 and BBC2, and published in The Rialto, The New European, The Interpreter’s House; and with Italian translations in Versodove. She has work forthcoming in Under the Radar, Finished Creatures and The African and Black Diaspora International Journal.

You can buy a copy of ‘Her Lost Language’ here.

Her Lost Language

English mouths are made of cloth

stitched, pulled apart with every word

Her life is mispronounced.

She cooks beef jollof rice for one;

braves the dark communal hall:

a giant’s throat when he is lying down.

He’s swallowed muffled voices,

stale breath of food and cigarettes.

The lift is shaped by urine.

The sky’s a coffin lid.

Back in her village, days from Lagos,

hills took on the shape of God,

scant clouds the colour of her tongue.

Now she must walk past ghosts who leer like men,

to eat fast food from styrofoam,

binging to forget her scars

are less important every day,

when words must match

from one assessment to the next.

Back in her block, the lift vibrates

like an assault or panic rammed

beneath her skin by soldiers taking turns.

She skypes to smile at parents

aging in their Sunday clothes.

They say more teachers have been raped.

A baobab tree is balanced on her father’s head.

When the connection fails,

she flicks to channel Save Yourself.

A pastor bangs the podium, demands her Hallelujah.

She kneels to pray her papers will be stamped –

passport wrapped in green batik.

Pastor screams Give thanks.

In

In  Thatcher tried to do a Richard II in the late days of her reign.

Thatcher tried to do a Richard II in the late days of her reign.  Jane Burn’s poem ‘THE COMMUNITY CHARGE, HOW WILL IT WORK FOR YOU?’ takes us back to the detail of this regressive tax, the anger and protests it caused. ‘How will it affect six heads in a poor house?/ Don’t register, Don’t Pay, Don’t Collect./ It does not matter what you earn or own – / a duke would pay the same as a dustman.’ I remember a lot us were up in court for non-payment; I left for London at the time, leaving my unpaid bill behind. And although we were to suffer another seven years of Tory rule, Thatcher was thrown out on her arse. ‘It was like every Christmas come at once/ when we knew that we’d won, then she said/ We’re leaving Downing Street/ and we knew ding dong, that the witch was dead.’ Such levels of protest seem to have been beaten out of the working classes. But more than ever, I feel we are in a time similar to, if not worse than the days of Thatcher. The Tories have squeezed/sliced/butchered local tax revenues, so the Council Tax is on the rise; and the state is swiftly shriveling, offloading services to private enterprise. We surely need a modern day Wat Tyler, doesn’t matter if he or she lives in Kent (although that is quite a handy launch point), any place will do; and make sure you bring all your mates.

Jane Burn’s poem ‘THE COMMUNITY CHARGE, HOW WILL IT WORK FOR YOU?’ takes us back to the detail of this regressive tax, the anger and protests it caused. ‘How will it affect six heads in a poor house?/ Don’t register, Don’t Pay, Don’t Collect./ It does not matter what you earn or own – / a duke would pay the same as a dustman.’ I remember a lot us were up in court for non-payment; I left for London at the time, leaving my unpaid bill behind. And although we were to suffer another seven years of Tory rule, Thatcher was thrown out on her arse. ‘It was like every Christmas come at once/ when we knew that we’d won, then she said/ We’re leaving Downing Street/ and we knew ding dong, that the witch was dead.’ Such levels of protest seem to have been beaten out of the working classes. But more than ever, I feel we are in a time similar to, if not worse than the days of Thatcher. The Tories have squeezed/sliced/butchered local tax revenues, so the Council Tax is on the rise; and the state is swiftly shriveling, offloading services to private enterprise. We surely need a modern day Wat Tyler, doesn’t matter if he or she lives in Kent (although that is quite a handy launch point), any place will do; and make sure you bring all your mates. One of the darker but also more playful songs by Tom Waits is “

One of the darker but also more playful songs by Tom Waits is “ But I also think that people are amazing in the projects they engage in. My son watches endless YouTube videos of everyday inventors – people who try to

But I also think that people are amazing in the projects they engage in. My son watches endless YouTube videos of everyday inventors – people who try to  Anna Saunders’ beautiful poem “Befriending the Butcher’, tells the story of a working class life that furthers this idea that you never know what a person might be. “He spent his days dressing flesh/ preparing Primal Cuts and his nights – carving wood,/ reading brick-heavy biographies of Larkin or Keats.” And what you start will carry you into later life, “There we sat, …./ on chairs as dark and immense as the Wagner/ which poured into the room,” So think again when you’re at the checkout, at the bar, chatting with the postman or the butcher, for you never know what they may be building when they get back home and hide themselves away in the attic or the shed.

Anna Saunders’ beautiful poem “Befriending the Butcher’, tells the story of a working class life that furthers this idea that you never know what a person might be. “He spent his days dressing flesh/ preparing Primal Cuts and his nights – carving wood,/ reading brick-heavy biographies of Larkin or Keats.” And what you start will carry you into later life, “There we sat, …./ on chairs as dark and immense as the Wagner/ which poured into the room,” So think again when you’re at the checkout, at the bar, chatting with the postman or the butcher, for you never know what they may be building when they get back home and hide themselves away in the attic or the shed.

Ben Banyard’s poem ‘This is Not Your Beautiful Game’ nicely captures the reality and sometime excitement of such wind-blown support, “This is not Wembley or the Emirates./We’re broken cement terraces, rusting corrugated sheds,/remnants of barbed wire, crackling tannoy.” You don’t get prawn sandwiches here (not that you would want them), it’s “pies described only as ‘meat’,/cups of Bovril, instant coffee, stewed tea.” But out of such masochistic adversity, comes great strength, as well as pride. “Little boys who support our club learn early/how to handle defeat and disappointment…./We are the English dream, the proud underdog/twitching hind legs in its sleep.” It is never too late for some players’ dreams; many have risen out of the lower ranks, to play in the Premier League, like Chris Smalling, Charlie Austin, Jimmy Bullard, Troy Deeney, and Jamie Vardy. And of course not forgetting Coventry’s own Trevor Peake, who at the age of 26 was bought from Lincoln City and was part of the 1987 FA Cup winning side.

Ben Banyard’s poem ‘This is Not Your Beautiful Game’ nicely captures the reality and sometime excitement of such wind-blown support, “This is not Wembley or the Emirates./We’re broken cement terraces, rusting corrugated sheds,/remnants of barbed wire, crackling tannoy.” You don’t get prawn sandwiches here (not that you would want them), it’s “pies described only as ‘meat’,/cups of Bovril, instant coffee, stewed tea.” But out of such masochistic adversity, comes great strength, as well as pride. “Little boys who support our club learn early/how to handle defeat and disappointment…./We are the English dream, the proud underdog/twitching hind legs in its sleep.” It is never too late for some players’ dreams; many have risen out of the lower ranks, to play in the Premier League, like Chris Smalling, Charlie Austin, Jimmy Bullard, Troy Deeney, and Jamie Vardy. And of course not forgetting Coventry’s own Trevor Peake, who at the age of 26 was bought from Lincoln City and was part of the 1987 FA Cup winning side.

Catherine Graham’s poem Market Scene, Northern Town evokes this scene of bustling activity and its mix of goods: “The lidded stalls are laden with everything/from home-made cakes to hand-me-downs.” This is a tradition that is woven into daily activities: “They’ve/spilled out from early morning mass,/freshly blessed and raring to bag a bargain,/scudding across the cobbles, like shipyard workers/knocking off.” And from the food bought, you will “smell the pearl barley,/carrots, potatoes and onions, the stock bubbling/nicely in the pot.” We shouldn’t be too doom laden when it comes to the decline in markets, because they haven’t died out altogether, and I’m not sure they will. I for one would miss the market trader shouting, ‘Come ‘an ‘av a look. Pand a bowl!’

Catherine Graham’s poem Market Scene, Northern Town evokes this scene of bustling activity and its mix of goods: “The lidded stalls are laden with everything/from home-made cakes to hand-me-downs.” This is a tradition that is woven into daily activities: “They’ve/spilled out from early morning mass,/freshly blessed and raring to bag a bargain,/scudding across the cobbles, like shipyard workers/knocking off.” And from the food bought, you will “smell the pearl barley,/carrots, potatoes and onions, the stock bubbling/nicely in the pot.” We shouldn’t be too doom laden when it comes to the decline in markets, because they haven’t died out altogether, and I’m not sure they will. I for one would miss the market trader shouting, ‘Come ‘an ‘av a look. Pand a bowl!’