In 1381 Wat Tyler led the peasant revolt against Richard II’s poll tax (Richard was a uppity fifteen year old at the time). The Black Death of thirty-five years prior had wiped out more than a third of the population, leading to a shortage of labour, thus increasing the power of the peasantry. The lords and landowners wanted to raise more money, in particular as the war with France was proving very costly. The peasants wanted a wage rise, the aristocracy wanted a poll tax. Things got a bit out of hand when Tyler’s lot marched on London from Kent, riots ensued, the King gave in, but was weak to implement promises, and Tyler had his neck slashed.

In 1381 Wat Tyler led the peasant revolt against Richard II’s poll tax (Richard was a uppity fifteen year old at the time). The Black Death of thirty-five years prior had wiped out more than a third of the population, leading to a shortage of labour, thus increasing the power of the peasantry. The lords and landowners wanted to raise more money, in particular as the war with France was proving very costly. The peasants wanted a wage rise, the aristocracy wanted a poll tax. Things got a bit out of hand when Tyler’s lot marched on London from Kent, riots ensued, the King gave in, but was weak to implement promises, and Tyler had his neck slashed.

Thatcher tried to do a Richard II in the late days of her reign. The Community Charge, aka the Poll Tax, was the introduction of a per head tax, which negatively affected those on low incomes, but was popular with blue blood Tories. But like Tyler and his acolytes, the working class were having none of it. There were riots across the country, with a major disturbance in London where police cars had wooden poles put through the windows. As I’m sure most readers know, this is what brought the end of Thatcher; not by a general election but by her own party, who finally swallowed their fear allowing the charismatic, alpha male orator John Major to win an election nobody at the time predicted.

Thatcher tried to do a Richard II in the late days of her reign. The Community Charge, aka the Poll Tax, was the introduction of a per head tax, which negatively affected those on low incomes, but was popular with blue blood Tories. But like Tyler and his acolytes, the working class were having none of it. There were riots across the country, with a major disturbance in London where police cars had wooden poles put through the windows. As I’m sure most readers know, this is what brought the end of Thatcher; not by a general election but by her own party, who finally swallowed their fear allowing the charismatic, alpha male orator John Major to win an election nobody at the time predicted.

Jane Burn’s poem ‘THE COMMUNITY CHARGE, HOW WILL IT WORK FOR YOU?’ takes us back to the detail of this regressive tax, the anger and protests it caused. ‘How will it affect six heads in a poor house?/ Don’t register, Don’t Pay, Don’t Collect./ It does not matter what you earn or own – / a duke would pay the same as a dustman.’ I remember a lot us were up in court for non-payment; I left for London at the time, leaving my unpaid bill behind. And although we were to suffer another seven years of Tory rule, Thatcher was thrown out on her arse. ‘It was like every Christmas come at once/ when we knew that we’d won, then she said/ We’re leaving Downing Street/ and we knew ding dong, that the witch was dead.’ Such levels of protest seem to have been beaten out of the working classes. But more than ever, I feel we are in a time similar to, if not worse than the days of Thatcher. The Tories have squeezed/sliced/butchered local tax revenues, so the Council Tax is on the rise; and the state is swiftly shriveling, offloading services to private enterprise. We surely need a modern day Wat Tyler, doesn’t matter if he or she lives in Kent (although that is quite a handy launch point), any place will do; and make sure you bring all your mates.

Jane Burn’s poem ‘THE COMMUNITY CHARGE, HOW WILL IT WORK FOR YOU?’ takes us back to the detail of this regressive tax, the anger and protests it caused. ‘How will it affect six heads in a poor house?/ Don’t register, Don’t Pay, Don’t Collect./ It does not matter what you earn or own – / a duke would pay the same as a dustman.’ I remember a lot us were up in court for non-payment; I left for London at the time, leaving my unpaid bill behind. And although we were to suffer another seven years of Tory rule, Thatcher was thrown out on her arse. ‘It was like every Christmas come at once/ when we knew that we’d won, then she said/ We’re leaving Downing Street/ and we knew ding dong, that the witch was dead.’ Such levels of protest seem to have been beaten out of the working classes. But more than ever, I feel we are in a time similar to, if not worse than the days of Thatcher. The Tories have squeezed/sliced/butchered local tax revenues, so the Council Tax is on the rise; and the state is swiftly shriveling, offloading services to private enterprise. We surely need a modern day Wat Tyler, doesn’t matter if he or she lives in Kent (although that is quite a handy launch point), any place will do; and make sure you bring all your mates.

Jane Burn is a writer originally from South Yorkshire, who now lives and works in the North East, UK. Her poems have been featured in magazines such as The Rialto, Under The Radar, Butcher’s Dog, Iota Poetry, And Other Poems, The Black Light Engine Room and many more, as well as anthologies from the Emma Press, Beautiful Dragons, Seren, and The Emergency Poet. Her pamphlets include Fat Around the Middle, published by Talking Pen and Tongues of Fire published by the BLER Press. Her first full collection, nothing more to it than bubbles has been published by Indigo Dreams. She has had four poems longlisted in the National Poetry Competition between 2014 – 2017, was commended and highly commended in the Yorkmix 2014 & 2015, won the inaugural Northern Writes Poetry Competition in 2017 and came second in the Welsh International Poetry Competition 2017.

THE COMMUNITY CHARGE

HOW WILL IT WORK FOR YOU?

How will it affect six heads in a poor house?

Don’t register, Don’t Pay, Don’t Collect.

It does not matter what you earn or own –

a duke would pay the same as a dustman.

Buckingham Palace as much as your nan.

Our mum, taking us four kids to Barnsely,

shouting at them at the Town Hall, how

am I meant to pay for all of these?

Fuck the working classes, Thatcher thought.

To those that stood and marched and fought,

raised placards, BREAK THE TORY POLL TAX –

thank you.

To those, battered to the ground by Thatcher’s thugs –

thank you.

To the APTUs, speaking for those who had no voice –

to the ones who helped us see that we had a choice,

thank you.

It was like every Christmas come at once

when we knew that we’d won, then she said

We’re leaving Downing Street

and we knew ding dong, that the witch was dead.

Thatcher, you wore

a tyrant’s crown.

Thatcher, you’re going

to hell.

Thatcher, you failed

to learn our strength.

Thatcher, you’re going

down.

THE COMMUNITY CHARGE…HOW WILL IT WORK FOR YOU? –

taken from a government leaflet explaining the new charge.

Don’t register, Don’t Pay, Don’t Collect. – APTU slogan.

a duke would pay the same as a dustman. – Nicholas Ridley,

Conservative Secretary of State for the Environment

We’re leaving Downing Street – part of Margaret Thatcher’s speech

on leaving Number 10

I have just received a great little publication by my friend and comrade in poetry,

I have just received a great little publication by my friend and comrade in poetry,  Mike Gallagher’s poem ‘Different Perspectives’ juxtaposes two examples of oppression; the first ‘Morant Bay, Jamaica, Seventeen Fifties,/ in close order a line of black women/ file up a ship’s gangway, overladen/ panniers of coal balanced on their heads.’ There is some comparison here with Mike’s own heritage, as

Mike Gallagher’s poem ‘Different Perspectives’ juxtaposes two examples of oppression; the first ‘Morant Bay, Jamaica, Seventeen Fifties,/ in close order a line of black women/ file up a ship’s gangway, overladen/ panniers of coal balanced on their heads.’ There is some comparison here with Mike’s own heritage, as

For those of us not able to do so, we are very lucky to have the likes of multi-talented Jemima Foxtrot who in a poem from her debut collection, All Damn Day, does what a lot of great poets do, allows us to dream. She takes a somewhat Manichean outlook that fits with the division we all feel in what we would like to do: “A half of me wants to exist in a tepee,/breed children who can braid hair and catch rabbits./Drink cocoa from half Coke cans twice a year/on their birthdays, the edges folded inwards/to protect their sleepy lips, cheap gloves to buffer their fingers,/precious marshmallows pronged on long mossy sticks.” However, such ‘rural and romantic poverty’ does not always fit with present circumstance, so we dream elsewhere. “If I were rich/I’d eat asparagus and egg,/in my Egyptian-cotton-coated bed, for breakfast. Bad. Ass./You’d find me in my limo, got a driver called Ricardo,/wears a nice hat. That’s that. Bad. Ass.” And in this dream we may travel to such places as Dorling suggests, but Jemima insightfully shows what lies at the heart these ‘hypocrisies’ we sit in, and how a division of one half or another can lead us all to a false sense of what it is we are after. “Capital has split my dreams in two /like a grapefruit./And I want both. And I want both.”

For those of us not able to do so, we are very lucky to have the likes of multi-talented Jemima Foxtrot who in a poem from her debut collection, All Damn Day, does what a lot of great poets do, allows us to dream. She takes a somewhat Manichean outlook that fits with the division we all feel in what we would like to do: “A half of me wants to exist in a tepee,/breed children who can braid hair and catch rabbits./Drink cocoa from half Coke cans twice a year/on their birthdays, the edges folded inwards/to protect their sleepy lips, cheap gloves to buffer their fingers,/precious marshmallows pronged on long mossy sticks.” However, such ‘rural and romantic poverty’ does not always fit with present circumstance, so we dream elsewhere. “If I were rich/I’d eat asparagus and egg,/in my Egyptian-cotton-coated bed, for breakfast. Bad. Ass./You’d find me in my limo, got a driver called Ricardo,/wears a nice hat. That’s that. Bad. Ass.” And in this dream we may travel to such places as Dorling suggests, but Jemima insightfully shows what lies at the heart these ‘hypocrisies’ we sit in, and how a division of one half or another can lead us all to a false sense of what it is we are after. “Capital has split my dreams in two /like a grapefruit./And I want both. And I want both.” At the birth of my first son, after a somewhat traumatic first week of his life, my father said to me, in his dry wit, “You’ve a lifetime of worry ahead of you. When you’re 80 and he’s 50, you’ll still feel the same.” Now my father is in his 80s, for me the worry works both ways, to my teenage sons as well as my parents. The greatest parental experience I have had is becoming a stay-at-home/househusband/underling of my two sons some eight years ago. I was brought front stage on the gender divide of parenting; evidenced at first hand the plates mothers are juggling, as many of my new plates smashed on the floor.

At the birth of my first son, after a somewhat traumatic first week of his life, my father said to me, in his dry wit, “You’ve a lifetime of worry ahead of you. When you’re 80 and he’s 50, you’ll still feel the same.” Now my father is in his 80s, for me the worry works both ways, to my teenage sons as well as my parents. The greatest parental experience I have had is becoming a stay-at-home/househusband/underling of my two sons some eight years ago. I was brought front stage on the gender divide of parenting; evidenced at first hand the plates mothers are juggling, as many of my new plates smashed on the floor. My father was one of them, and so was David Cooke’s, whose father opted for retirement in his very early fifties, and is the subject of his poem, “Work”. His father was “a ‘man’s man’ my mother said, who needed/a joke to keep him going, and something to get him up in the morning besides/a late stroll to place his bets at Coral.” As a young son or daughter, the roles of your parents are defined by their actions; of what they do, and in them days it was the father who was out all day at work. So when he is made redundant, he is lost. “I’d learn that no one’s indispensable./So after he’d botched a shed, dug the pond/and built a rockery, the time was ripe/for change.” They had worked all their lives and didn’t want to lay fallow on the dole. My own father went on to do different jobs, as did David’s who “With a clapped-out van and a mate,/he started again on small extensions.”

My father was one of them, and so was David Cooke’s, whose father opted for retirement in his very early fifties, and is the subject of his poem, “Work”. His father was “a ‘man’s man’ my mother said, who needed/a joke to keep him going, and something to get him up in the morning besides/a late stroll to place his bets at Coral.” As a young son or daughter, the roles of your parents are defined by their actions; of what they do, and in them days it was the father who was out all day at work. So when he is made redundant, he is lost. “I’d learn that no one’s indispensable./So after he’d botched a shed, dug the pond/and built a rockery, the time was ripe/for change.” They had worked all their lives and didn’t want to lay fallow on the dole. My own father went on to do different jobs, as did David’s who “With a clapped-out van and a mate,/he started again on small extensions.” Readers of this blog are well aware of the impact Thatcher’s policies had on the coal mining industry during the 1980s. There have been a number of poems addressing the experience faced by the miners in their fight to secure the livelihoods. However, the impact was much wider than just those working at the coalface (sic). Besides the local shops gaining from a miner’s income, there were also those who delivered the coal – the coal merchants.

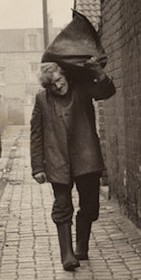

Readers of this blog are well aware of the impact Thatcher’s policies had on the coal mining industry during the 1980s. There have been a number of poems addressing the experience faced by the miners in their fight to secure the livelihoods. However, the impact was much wider than just those working at the coalface (sic). Besides the local shops gaining from a miner’s income, there were also those who delivered the coal – the coal merchants. Patrick Barron’s poem “The Coalmen” takes the point of view of a young child looking out their bedroom window at these black and grey men, carrying huge sacks weighing up to 50 kg, “as if they were carrying their own mothers across a river.” There is something of the mythical about these men, as though they were in disguise, as though they weren’t meant to be seen, shadows almost.

Patrick Barron’s poem “The Coalmen” takes the point of view of a young child looking out their bedroom window at these black and grey men, carrying huge sacks weighing up to 50 kg, “as if they were carrying their own mothers across a river.” There is something of the mythical about these men, as though they were in disguise, as though they weren’t meant to be seen, shadows almost.