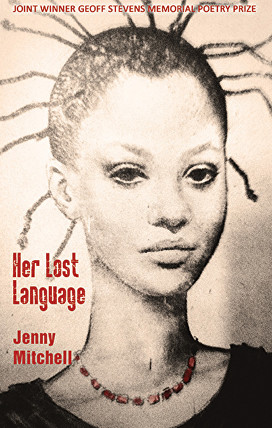

Today’s guest post is by Jenny Mitchell. Jenny was Joint winner of the Geoff Stevens Memorial Poetry Prize, run by Indigo Dreams Publishing, with her beautiful collection ‘Her Lost Language’. Paul McGrane of the Poetry Society, described the book as ‘a unique insight into a family history that invites you to re-imagine your own. I love this book and so will you!” You can buy a copy of the book here.

Jenny has given us the title poem from her book; a poignant depiction of life as a woman against a backdrop of terror and kidnap and the lack of refuge for those who escape.

*********************************

“The title poem for my debut collection, Her Lost Language, feels a bit like a ‘cuckoo’ in that I usually write about the legacies of British transatlantic enslavement, with direct reference to Jamaica. This seems to be where I find my voice, and can cover subjects from the maternal, food, past, present and future.

“The title poem for my debut collection, Her Lost Language, feels a bit like a ‘cuckoo’ in that I usually write about the legacies of British transatlantic enslavement, with direct reference to Jamaica. This seems to be where I find my voice, and can cover subjects from the maternal, food, past, present and future.

But the poem Her Lost Language was inspired by reports of Boko Haram in Nigeria, and their kidnapping/abuse/murder of girls and women, especially those seeking an education.

The articles about them seemed to coincide with more and more reports of a ‘hostile’ environment in the UK for immigrants and asylum-seekers.

I wanted to write about a woman who, having faced inhuman physical abuse, was being forced to endure the trauma of being ‘a stranger in a strange land’ that does not offer refuge.

I often write without knowing exactly what I mean but re-reading the poem I see that it’s very oral, lots about food and the sheer loneliness that can be symbolised in eating alone. I wonder if this is a metaphor for someone who cannot speak her language to anyone – a real language and an internal/emotional one – so ‘compensates’ by eating? Is she trying to cope by stuffing words down with food? Is cooking also a way to ‘recapture’ home?

It feels clear on re-reading the poem that the environment I describe is not just ‘hostile’ for the character but for everyone who has to live in it. The phrase, ‘A lift shaped by urine is’, to me, about real suffering – for those that have to endure it and those that cause the offence in the first place. How alienated do you have to be, to literally piss where you live?

It feels clear on re-reading the poem that the environment I describe is not just ‘hostile’ for the character but for everyone who has to live in it. The phrase, ‘A lift shaped by urine is’, to me, about real suffering – for those that have to endure it and those that cause the offence in the first place. How alienated do you have to be, to literally piss where you live?

The fact that the character has come from a place where the hills are shaped like God says something, to me, about what we have lost – ‘God’ as nature. Instead, the character in the poem looks for ‘God’ in a pastor who is remote, on television and instructing her to Give thanks when she lives and breathes suffering.

It’s always great to know what other people think so if you’d like to send your comments about this, or any of my poems, get in touch on Twitter @jennymitchellgo, or in the comments section below.”

Jenny Mitchell is joint winner of the Geoff Stevens’ Memorial Poetry Prize (Indigo Dreams Publishing). Her work has been broadcast on Radio 4 and BBC2, and published in The Rialto, The New European, The Interpreter’s House; and with Italian translations in Versodove. She has work forthcoming in Under the Radar, Finished Creatures and The African and Black Diaspora International Journal.

You can buy a copy of ‘Her Lost Language’ here.

Her Lost Language

English mouths are made of cloth

stitched, pulled apart with every word

Her life is mispronounced.

She cooks beef jollof rice for one;

braves the dark communal hall:

a giant’s throat when he is lying down.

He’s swallowed muffled voices,

stale breath of food and cigarettes.

The lift is shaped by urine.

The sky’s a coffin lid.

Back in her village, days from Lagos,

hills took on the shape of God,

scant clouds the colour of her tongue.

Now she must walk past ghosts who leer like men,

to eat fast food from styrofoam,

binging to forget her scars

are less important every day,

when words must match

from one assessment to the next.

Back in her block, the lift vibrates

like an assault or panic rammed

beneath her skin by soldiers taking turns.

She skypes to smile at parents

aging in their Sunday clothes.

They say more teachers have been raped.

A baobab tree is balanced on her father’s head.

When the connection fails,

she flicks to channel Save Yourself.

A pastor bangs the podium, demands her Hallelujah.

She kneels to pray her papers will be stamped –

passport wrapped in green batik.

Pastor screams Give thanks.

“Cardiff has one of the oldest BAME populations in the UK. However, it wasn’t a slave town like Bristol. The majority of the Black population were merchant seamen – who settled in Cardiff’s docks area, or Tiger Bay as it was known back then. My grandfather came to Cardiff via a familiar route in the 1890’s.

“Cardiff has one of the oldest BAME populations in the UK. However, it wasn’t a slave town like Bristol. The majority of the Black population were merchant seamen – who settled in Cardiff’s docks area, or Tiger Bay as it was known back then. My grandfather came to Cardiff via a familiar route in the 1890’s.  Gradually people migrated to other parts of Cardiff, My grandparents moved out in the 1940’s. Unfortunately my grandfather was on a ship which was torpedoed during World War 2 – so we never met. I grew up in what I jokingly referred to later as a Black & White family with a ‘coloured’ telly…. It’s funny when you’re a child, you don’t think of yourself as a colour…. I discovered I was black accidentally. We would always watch the news at teatime. It was sometime around 1972, and the newsreader barked “and the Blacks are rioting in…”. It was somewhere in London. I said, ‘Dad – who are the blacks?’. My dad looked at me quizzically and said ‘We are son…’. It was a light-bulb moment. “Aaaah – that’s why people call me funny names at school”, I thought. They were strange times – ‘

Gradually people migrated to other parts of Cardiff, My grandparents moved out in the 1940’s. Unfortunately my grandfather was on a ship which was torpedoed during World War 2 – so we never met. I grew up in what I jokingly referred to later as a Black & White family with a ‘coloured’ telly…. It’s funny when you’re a child, you don’t think of yourself as a colour…. I discovered I was black accidentally. We would always watch the news at teatime. It was sometime around 1972, and the newsreader barked “and the Blacks are rioting in…”. It was somewhere in London. I said, ‘Dad – who are the blacks?’. My dad looked at me quizzically and said ‘We are son…’. It was a light-bulb moment. “Aaaah – that’s why people call me funny names at school”, I thought. They were strange times – ‘ The poem I have chosen from my collection, has to be ‘On the death of Muhammad Ali’. A) Originally, it was one of my poems that Eric Ngalle Charles chose for his ‘

The poem I have chosen from my collection, has to be ‘On the death of Muhammad Ali’. A) Originally, it was one of my poems that Eric Ngalle Charles chose for his ‘