For most of you, today’s guest feature by Setareh Ebrahimi will really put into perspective what lockdown means when it goes on for years and years against your will. The poem ‘Like Grace Coddington’ comes from Setareh’s debut pamphlet In My Arms, from Bad Betty Press. You can buy it for £3, here:

**********************

“Engaging with the general lockdown reaction on social media has shown me how different groups of people have taken it – there are those that are, rightfully panicking, tearing their hair out, thrashing, screaming at the sky, denouncing their gods; and those, like myself, who climatized well due to having experienced some form of lockdown in their life.

“Engaging with the general lockdown reaction on social media has shown me how different groups of people have taken it – there are those that are, rightfully panicking, tearing their hair out, thrashing, screaming at the sky, denouncing their gods; and those, like myself, who climatized well due to having experienced some form of lockdown in their life.

I was never able to write about abuse or race until I realised I needed to talk about them a certain amount first. On social media I’ve seen posts like, ‘People be complaining about lockdown, brown girls been under lockdown their whole lives.’ Of course this hides a wealth of pain, and naturally we make jokes to cover it up.

Growing up with my dad, existence and isolation were the same thing; I wasn’t even allowed to see my family or talk to them on the telephone, or talk openly to my mother or sister who lived in the same house as me. The one hour of exercise we are allowed now, was pretty much the extent of my outdoor existence for years. Being 1-2 hours late after school once, when I was in Year 8 because I wanted to play in a field with my friends, didn’t end well for me. My experience was massively infantalised; I’m embarrassed to write that I was playing imaginary games with little kiddy toys into my late teens – my sister was six years younger than me and essentially the only friend I  had.

had.

All I could really do was read, depending on what library books I could get my hands on or what I could pick up at the supermarket or in shops near places my mum needed to run errands at. Even then I remember being shouted at for reading Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, till I had a nervous breakdown. Going to the supermarket or the laundry with my mum was an outing. Waking up in the morning meant thinking of hours in the form of four quarters, and counting them off till bedtime. I spent a lot of time wondering if I’d be better off dead, whether I should blow my brains out or whether I was real or invisible. The ensuing adult years of poverty, desperation, drug use, mental health issues and loneliness as a result weren’t great either.

A friend of mine who is also BAME and a writer, confirmed to me that the effects of isolation make you feel crazy. Nothing exists outside your own four walls. She used to not know what her city looked like. A small car ride out seemed like a holiday. The only outdoors she saw was the single road to her school; this road expanded when she hit college but it was still marked with curfews. She literally wasn’t allowed to leave her room in her house for the majority of her childhood up till when she left, at around 21.

Did you ever think that there were a lot of invisible people living in lockdown before this pandemic? There are people everywhere living sad lives, and then they die quietly. I’m left with the lingering frustration that things only become an issue when they affect people en masse, or affect those with a voice.

Did you ever think that there were a lot of invisible people living in lockdown before this pandemic? There are people everywhere living sad lives, and then they die quietly. I’m left with the lingering frustration that things only become an issue when they affect people en masse, or affect those with a voice.

My whole concept of time is different, I could wait and wait and wait, and I won’t know if half an hour has passed or five. I can fit into small spaces, I can stare at wall for days. The appropriate endurance boundary lies slack. I wrote in my poem, ‘Glittery Fairy Princess’, ‘The rest of the party was spent/like most of my time,/patiently observing the passage/of my own life.’

My main issue now is keeping my baby contained to a top floor flat without a lift. For many people, lockdown isn’t romantic, school’s out, barbecue garden party. It’s interesting to watch people try to create new rituals, as we have done.”

Setareh Ebrahimi is an Iranian-British poet living and working in Faversham, Kent. She completed her Bachelor’s in English Literature from The University of Westminster in 2014, and her Master’s in English and American Literature from The University of Kent in 2016. She has been published numerous times in various journals and magazines, including Brittle Star, Confluence, and Ink Sweat & Tears. Her poetry has also been anthologised numerous times, most recently by Eibonviale Press. Setareh released her first pamphlet of poetry, In My Arms, from Bad Betty Press in 2018. She regularly performs her poetry in Kent and London, has hosted her own poetry evenings and leads writing workshops. Setareh is currently a contributing editor for Thanet Writers. In 2018 Setareh was one of the poets in residence of The Margate Bookie, at The Turner Contemporary Gallery.

Like Grace Coddington

We return to revaluate

what we have control over;

the remits of our bodies, we hope.

You get these little tufts that stick

out just like your daughter’s.

You suggest a buzzcut,

I try not to let my enthusiasm

for a mohawk show.

I think it would be hot,

imagine it post-filter

with comments and reactions,

it’s not just writers that think

of themselves in third person now

and displaced associations

are all we have,

screens, glass.

I’ve always felt my spirit

was in a body it didn’t look like,

longed for a pink or blue hair moment

unavailable to round brown girls

with hair the colour of tar

that just wouldn’t take.

But I want to join you,

could buy a few packs of purple dye

and repeatedly apply before revealing,

fluff it out like Grace Coddington.

We turn over the flat in search

of clipper heads,

not to count what we still have.

“The anthology ‘Onward/ Ymlaen!’ published by Culture Matters comprises left-wing poems from Cymru rather than ‘Wales’. Why do I stress this? As the

“The anthology ‘Onward/ Ymlaen!’ published by Culture Matters comprises left-wing poems from Cymru rather than ‘Wales’. Why do I stress this? As the  As co-editor of ‘

As co-editor of ‘ Jones’s own journey from Labour supporter to embracing the emerging Indy movement is one which truly reflects our politically fluid times.

Jones’s own journey from Labour supporter to embracing the emerging Indy movement is one which truly reflects our politically fluid times.

I try to watch the news once a day; more than that and it is really depressing. Alternatively it is infuriating, why do we need to see Royalty clapping in an obviously posed way with their children outside their front door which does not appear to be in a street where anyone else lives. When have they ever used the NHS?

I try to watch the news once a day; more than that and it is really depressing. Alternatively it is infuriating, why do we need to see Royalty clapping in an obviously posed way with their children outside their front door which does not appear to be in a street where anyone else lives. When have they ever used the NHS? Yesterday I made marmalade, from one of those tins of prepared Seville oranges; I knew they were good because my mother used them, rather secretly as she saw it as cheating. When I was quite small I remember going, in our fathers cab, to pick blackberries in

Yesterday I made marmalade, from one of those tins of prepared Seville oranges; I knew they were good because my mother used them, rather secretly as she saw it as cheating. When I was quite small I remember going, in our fathers cab, to pick blackberries in  My partner and I are both of an age where a store cupboard is normal. Our parents lived through the war so there were always a few tins and packets kept for emergencies. We order our shopping delivery fortnightly and have a kind of general store. We are trying not hoard and so far have managed to get roughly what we need. When our delivery arrives it gets washed, dried and put away. Sometimes the way we talk about what is happening reminds me of my childhood when food was still rationed and my parents were not very well off. My mother was a genius at making things stretch not just food but clothes too.

My partner and I are both of an age where a store cupboard is normal. Our parents lived through the war so there were always a few tins and packets kept for emergencies. We order our shopping delivery fortnightly and have a kind of general store. We are trying not hoard and so far have managed to get roughly what we need. When our delivery arrives it gets washed, dried and put away. Sometimes the way we talk about what is happening reminds me of my childhood when food was still rationed and my parents were not very well off. My mother was a genius at making things stretch not just food but clothes too. “For much of my life, I struggled with a range of symptoms which seemed to bare no correlation to one another. Chronic fatigue, an increasingly constant nausea level, violent aching without reason.

“For much of my life, I struggled with a range of symptoms which seemed to bare no correlation to one another. Chronic fatigue, an increasingly constant nausea level, violent aching without reason. My poem, ‘young man,’ was really one of my first explorations of this tension between distance and closeness. It felt like an act of empowerment, as I initially struggled to find work, to admit defeat. To acknowledge flaws, and to ironise them. As it turns out, to be vulnerable in life makes it far easier to be vulnerable on the page, and soon a body of work began to form around the experience of living within my own body.

My poem, ‘young man,’ was really one of my first explorations of this tension between distance and closeness. It felt like an act of empowerment, as I initially struggled to find work, to admit defeat. To acknowledge flaws, and to ironise them. As it turns out, to be vulnerable in life makes it far easier to be vulnerable on the page, and soon a body of work began to form around the experience of living within my own body.

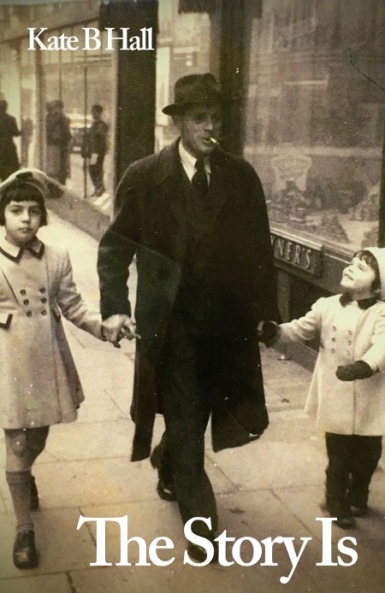

And as I looked for ways to complete my father’s portrait, I noticed how proud I am of him, how his work ideals and diligence have come to define him. Coming from a more working class background and without a university education, he wanted a different future for me, a future alien to him and his class, where more doors would be open with the promise of a good education.

And as I looked for ways to complete my father’s portrait, I noticed how proud I am of him, how his work ideals and diligence have come to define him. Coming from a more working class background and without a university education, he wanted a different future for me, a future alien to him and his class, where more doors would be open with the promise of a good education. “When we rang in the New Year, I don’t expect any of us thought our 2020 would include supermarket queues, panic buying, empty motorways, or an invisible Prime Minister, but here we are. The world is a quieter place, where we keep our distance from each other, do our weekly shop, and – in my case at least – spend far too much time online, seeking some kind of social interaction. For better or worse, our worlds have shrunk to our immediate neighbourhood, the few streets round us, the distance we can walk or cycle in an hour.

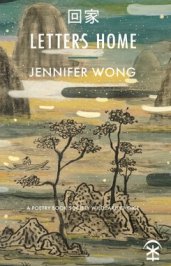

“When we rang in the New Year, I don’t expect any of us thought our 2020 would include supermarket queues, panic buying, empty motorways, or an invisible Prime Minister, but here we are. The world is a quieter place, where we keep our distance from each other, do our weekly shop, and – in my case at least – spend far too much time online, seeking some kind of social interaction. For better or worse, our worlds have shrunk to our immediate neighbourhood, the few streets round us, the distance we can walk or cycle in an hour. Many of the poems in my new book ‘

Many of the poems in my new book ‘

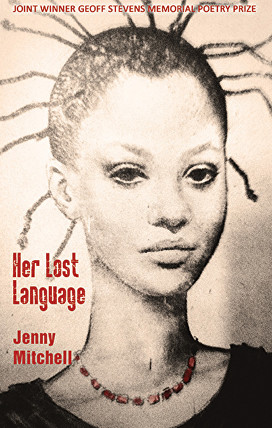

“The title poem for my debut collection, Her Lost Language, feels a bit like a ‘cuckoo’ in that I usually write about the legacies of British transatlantic enslavement, with direct reference to Jamaica. This seems to be where I find my voice, and can cover subjects from the maternal, food, past, present and future.

“The title poem for my debut collection, Her Lost Language, feels a bit like a ‘cuckoo’ in that I usually write about the legacies of British transatlantic enslavement, with direct reference to Jamaica. This seems to be where I find my voice, and can cover subjects from the maternal, food, past, present and future. It feels clear on re-reading the poem that the environment I describe is not just ‘hostile’ for the character but for everyone who has to live in it. The phrase, ‘A lift shaped by urine is’, to me, about real suffering – for those that have to endure it and those that cause the offence in the first place. How alienated do you have to be, to literally piss where you live?

It feels clear on re-reading the poem that the environment I describe is not just ‘hostile’ for the character but for everyone who has to live in it. The phrase, ‘A lift shaped by urine is’, to me, about real suffering – for those that have to endure it and those that cause the offence in the first place. How alienated do you have to be, to literally piss where you live? “Cardiff has one of the oldest BAME populations in the UK. However, it wasn’t a slave town like Bristol. The majority of the Black population were merchant seamen – who settled in Cardiff’s docks area, or Tiger Bay as it was known back then. My grandfather came to Cardiff via a familiar route in the 1890’s.

“Cardiff has one of the oldest BAME populations in the UK. However, it wasn’t a slave town like Bristol. The majority of the Black population were merchant seamen – who settled in Cardiff’s docks area, or Tiger Bay as it was known back then. My grandfather came to Cardiff via a familiar route in the 1890’s.  Gradually people migrated to other parts of Cardiff, My grandparents moved out in the 1940’s. Unfortunately my grandfather was on a ship which was torpedoed during World War 2 – so we never met. I grew up in what I jokingly referred to later as a Black & White family with a ‘coloured’ telly…. It’s funny when you’re a child, you don’t think of yourself as a colour…. I discovered I was black accidentally. We would always watch the news at teatime. It was sometime around 1972, and the newsreader barked “and the Blacks are rioting in…”. It was somewhere in London. I said, ‘Dad – who are the blacks?’. My dad looked at me quizzically and said ‘We are son…’. It was a light-bulb moment. “Aaaah – that’s why people call me funny names at school”, I thought. They were strange times – ‘

Gradually people migrated to other parts of Cardiff, My grandparents moved out in the 1940’s. Unfortunately my grandfather was on a ship which was torpedoed during World War 2 – so we never met. I grew up in what I jokingly referred to later as a Black & White family with a ‘coloured’ telly…. It’s funny when you’re a child, you don’t think of yourself as a colour…. I discovered I was black accidentally. We would always watch the news at teatime. It was sometime around 1972, and the newsreader barked “and the Blacks are rioting in…”. It was somewhere in London. I said, ‘Dad – who are the blacks?’. My dad looked at me quizzically and said ‘We are son…’. It was a light-bulb moment. “Aaaah – that’s why people call me funny names at school”, I thought. They were strange times – ‘ The poem I have chosen from my collection, has to be ‘On the death of Muhammad Ali’. A) Originally, it was one of my poems that Eric Ngalle Charles chose for his ‘

The poem I have chosen from my collection, has to be ‘On the death of Muhammad Ali’. A) Originally, it was one of my poems that Eric Ngalle Charles chose for his ‘ “It seems to me, that this global pandemic leaves me unable to write a thing except maybe clichés; tired phrases. I can’t write about it but writing about anything else seems unthinkable. I’m aware that for some poets I know, the opposite is true and poems are pouring out of them. One way or another we are all affected and not just in regards writing; some people find themselves unable to do anything productive whilst others throw themselves into activity – we find our own ways of dealing with the anxiety. There is a definition of trauma that makes a correlation between the perceived level of threat and the perceived level of helplessness we feel in response to it; essentially when an event overwhelms our ability to cope. The reverberations of this collective trauma will be around long after the lockdown ends.

“It seems to me, that this global pandemic leaves me unable to write a thing except maybe clichés; tired phrases. I can’t write about it but writing about anything else seems unthinkable. I’m aware that for some poets I know, the opposite is true and poems are pouring out of them. One way or another we are all affected and not just in regards writing; some people find themselves unable to do anything productive whilst others throw themselves into activity – we find our own ways of dealing with the anxiety. There is a definition of trauma that makes a correlation between the perceived level of threat and the perceived level of helplessness we feel in response to it; essentially when an event overwhelms our ability to cope. The reverberations of this collective trauma will be around long after the lockdown ends. I remember the helplessness I felt then too and how painting led me to writing this poem, ‘Drowning’. I wanted to send something cheerful and uplifting for this guest post but of the few more cheerful poems I’ve written nothing seemed right. I read a Facebook post a friend shared recently by someone who said the last time they were in lockdown was during the

I remember the helplessness I felt then too and how painting led me to writing this poem, ‘Drowning’. I wanted to send something cheerful and uplifting for this guest post but of the few more cheerful poems I’ve written nothing seemed right. I read a Facebook post a friend shared recently by someone who said the last time they were in lockdown was during the

internationally touring DJs and members of an all-female band of adults with learning difficulties. My aim wasn’t to get famous names but to talk to women who lived and breathed music in their everyday life, either professionally or at an amateur level.

internationally touring DJs and members of an all-female band of adults with learning difficulties. My aim wasn’t to get famous names but to talk to women who lived and breathed music in their everyday life, either professionally or at an amateur level.